SAO PAULO — Thiago Souza emerges from the barricades a man making history.

A single-file line spirals the Ibirapuera mall and spills onto the street. Hundreds watch as the man they call “Curitiba,” the guy with the giant backpack, glasses and Green Bay gear — Jordan Love jersey, Packers hoodie and hat — unsheathes his credit card and jabs his forefinger at a seating map. There. The first-ever ticket for an NFL game in South America.

Fine, maybe not the first ticket.

Today is Thursday, June 13, which was supposed to be the opening day of sales. Even local Ticketmaster staffers who’d been preparing for 20 days to manage this madness were surprised by the June 10 presale. In a belated bonus for the region’s presenting sponsor, the NFL abruptly added an exclusive sale for customers of XP, an investment bank based in Sao Paulo.

But, by Brazilian law, 10 percent of any such tickets must be sold in person. So, the mall’s box office bustled like a bank run. Panic hit social media. Ticketmaster’s online portal crammed 150,000 people into its digital waiting room. Only 15,000 pre-sale tickets were sold.

Some 250 miles away in Curitiba, Souza, a 36-year-old movie theater manager, bought two tickets … to an Anavitória concert for Dia Dos Namorados, Brazil’s Valentine’s Day. Sell those tickets, his wife said. Go to Sao Paulo. Don’t come back without our NFL tickets. He flipped the concert stubs for a Monday seat on an 11 p.m. bus, saw nothing afoot Tuesday at the mall, slept in a hostel and returned at 10 a.m. Wednesday.

Where is the line? Souza asked security. You are the line, they said.

Sunset. Sunrise. Souza loses his lawn chair in the excitement. Fellow campers shout “Curitiba!” as he pumps his phone and its digital receipt: four tickets behind the goalpost totaling 4,305 Brazilian reais ($766), roughly three times Brazil’s monthly minimum wage.

“I didn’t think, quite actually, how much it would cost,” Souza says through an interpreter. “I just needed to get the tickets.”

Gustavo Pires, the president of Sao Paulo tourism, predicted this hysteria. After Pires and a Brazilian delegation delivered their game proposal to the NFL, league commissioner Roger Goodell asked him why he thought the city would work. “If we had a 300,000-person stadium,” Pires replied, “we would sell out the 300,000 seats.”

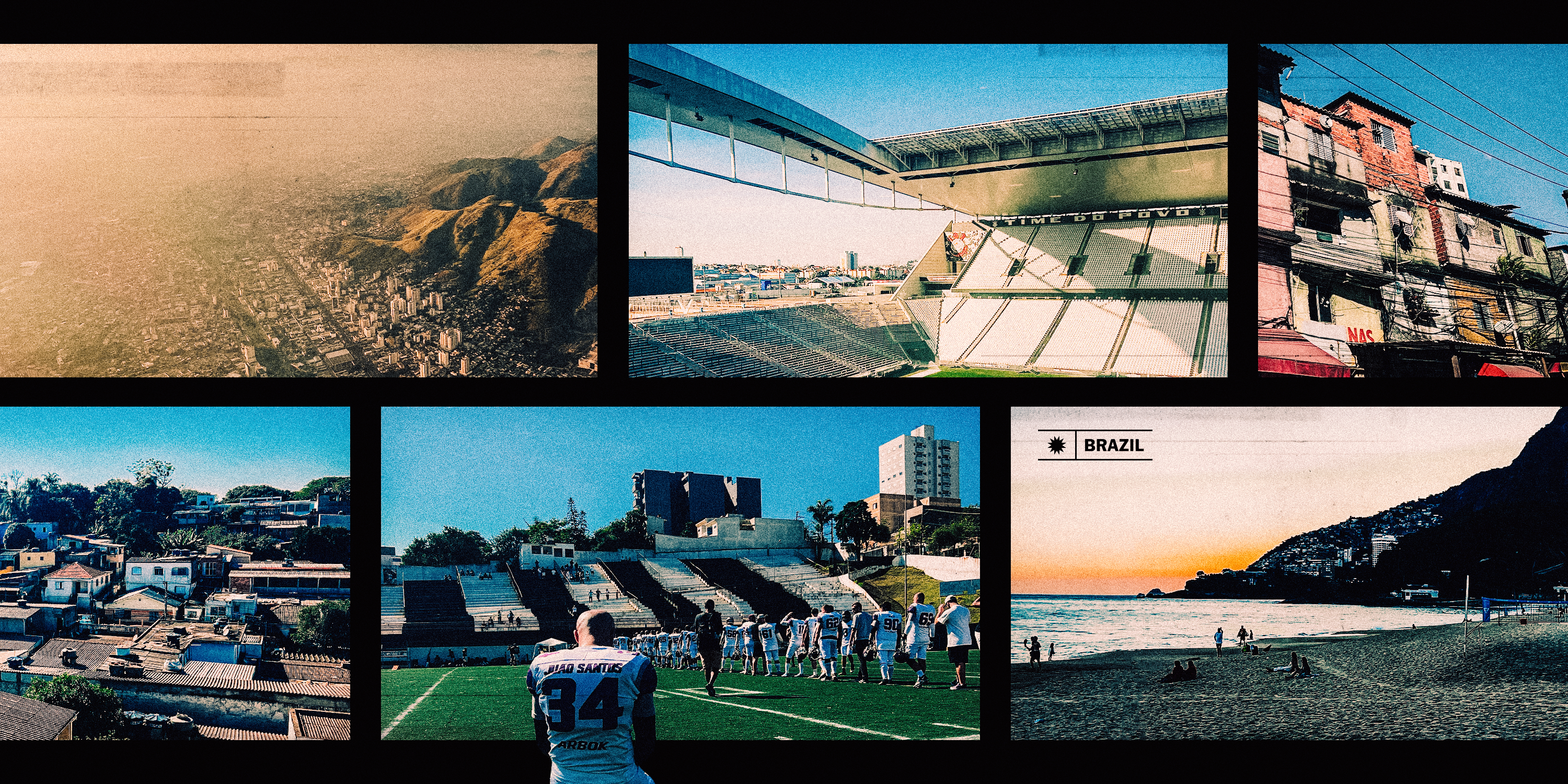

Fans flocked to the box office at Shopping Ibirapuera to buy tickets for the first NFL game in South America. (Brooks Kubena / The Athletic)

Just under 50,000 ticket-holders will enter Arena Corinthians on Friday when the Philadelphia Eagles and Green Bay Packers christen the NFL’s investment in a new continent. The league’s international series began after a 2005 one-off in Mexico City set the regular-season attendance record (103,467). Since 2007, the NFL has scheduled at least one regular-season game per year outside the United States: 39 in London, five in Mexico City, two in Frankfurt, two in Munich. Data, trial events and local legwork have compelled the NFL into a country that’s never hosted so much as an exhibition.

How deeply the NFL embeds into Brazilian life depends on how successfully the sport breaks through significant cultural, political and financial barriers. Football (American football) is a distant enigma to most of the Brazilian population (215.3 million), even among the wealthy who discovered the sport in private school or when studying in the States.

But enigmas can be lucrative when there’s an opportunity to view them up close. When asked how many new clients the pre-sale produced for XP, chief marketing officer Lisandro Lopez chuckled. “A lot,” he’d say, pointing to a public relations staffer in his high-rise office. “He’ll kill me if I tell you.”

As the NFL digs into the market share of a soccer-crazed country, it’s uncovering an audience with a history of limited access to live broadcasts, a passionate yet unwieldy football federation that needs funding and reformation and a pool of athletes who, like many Brazilians, chase dreams while straddling the poverty line.

The Athletic spent eight days in Sao Paulo exploring a football landscape that’s largely undefined. What does success look like for those involved? And how much interest will remain after the NFL is no longer a novelty?

Ha-ha! Hoo-hoo! Estamos nas finais! Ha-ha! Hoo-hoo! Estamos nas finais!

In Estádio Baetão, a state-owned complex neighboring Santo André, a jagged accordion of empty stone bleachers bookends artificial turf on one side, a rowdy four rows on the other. Under a derelict press box — rust and plywood exposed by a loose banner hung like an unbuttoned shirt — the spray of beer cans and fumes of smoke flares cover a crowd whose chant competes with a crackling PA system.

The field has been willed together: down markers made of PVC pipes, yard markers made of foam. If the sideline ambulance transports an injured player the game must be suspended until it returns.

This playoff contest is all but decided. Hard to tell with no scoreboard — the PA announcer is doing his damnedest — but the Santo André Werewolves are thrashing the Tatuapé Monsters. On the nameplates of their purple-trimmed jerseys, some sewed surnames, some nicknames: Ninja, G.I., King.

“Interceptação!” Ha-ha! Hoo-hoo! The Monsters quarterback has thrown his third straight pick, all to the same Werewolves defensive back. The level of play in the São Paulo Football League evokes a Darrell Royal quote, “Three things can happen when you pass, and two of ’em are bad.” A Werewolf runs for a touchdown, then kneels in prayer: 42-7. A guy dozes on the bleachers, a white shirt partly covering his sunburnt face.

Sophistication varies across Brazil’s rivaling football associations. Organized play began on Rio de Janeiro beaches in the 1980s, first birthing an annual “Carioca Bowl,” then the 2000 founding of what’s now known as the Confederação Brasileira de Futebol Americano. In 2016, some of the CBFA’s biggest teams formed an association to organize a national championship. So began the abbreviated BFA, which had two divisions and more than 60 teams from 2017-19.

Divorce followed the pandemic. The BFA now operates independently in a league run by its 21 teams. The CBFA’s board members chose to run their own championship and manage a soccer-like structure in which 300 teams are divided into regional leagues like the SPFL and compete for a national title.

Neither system is yet profitable. CBFA president Cris Kajiwara says each team needs nearly 200,000 reais (about $38,000) to compete annually. Players in both leagues buy their own equipment, spending as much as three times the nation’s monthly minimum wage on helmets, shoulder pads, pants and cleats. Brazilian manufacturers don’t make footballs, so players pay steep prices to the few sporting goods stores that import such equipment.

But as the final whistle blows at Estádio Baetão, it’s clear why any of them are doing this at all.

“Passion,” says João Batista, 39, the defensive back whose three interceptions sealed the win. He’s a stacker operator in Santos who spends a chunk of his monthly 3,000 real wages driving an hour “up the hill” every Saturday to play.

The Santo André Werewolves celebrate their win over the Tatuapé Monsters in a São Paulo Football League playoff game in Estádio Baetão. (Brooks Kubena / The Athletic)

BFA president Marcel Dantas says if the league’s budget increases, it will invest in rent for respectable stadiums; ESPN Brazil carried the 2019 final live, but networks have told him humble venues scare them away. As a sports non-profit association, the BFA is searching for sponsors, applying for federal funds and lobbying for laws that would allow private companies to count donations as tax credits.

But the CBFA holds the most political clout. It’s registered with the International Federation of American Football, a French-based organization that’s recognized by the International Olympic Committee, and therefore in a better position to secure federal funds through its oversight of the country’s national flag football teams. The confederation’s 250-team flag league supplied the Brazilian players who competed in the IFAF’s recently completed world championships in Finland.

Flag players foot bills, too. They paid their way to Finland for about 12,000 reais each ($2,136), the men’s team’s offensive coordinator, Leticia Ramos, says.

Felipe Aymoré, 20, is a 5-9, 172-pound defensive back. He’s a barista who eschewed college to train for the 2028 Olympics. His family and friends “don’t get why I’m doing this,” but they respect how he defends his “double journey,” the field via the coffee shop.

Kajiwara believes Olympic inclusion makes investing in flag football a critical strategy in growing interest in the padded sport. The NFL does, too. It’s supplying flags and footballs while the CBFA works with educational leaders to get the sport sponsored within schools. Pires says a 50-school trial program has already begun throughout Brazil and hinges mostly on student interest.

Dantas admires the CBFA’s flag efforts, but the BFA is focused on building a respectable and televised padded league. Dantas and Kajiwara both agree dividing federal funds between the leagues diminishes the impact the money would otherwise have if they were unified. They’ve begun informal talks about realignment.

“We’re in the way of each other,” says Bruno Barandas, head coach of the BFA’s Vasco Admirals.

Barandas, 30, has hitched his career to the sport’s success. He dropped out of law school to join the Admirals as a quarterbacks coach in 2015. A well-connected local helped push his resume to Georgetown University, and in 2017 Bruno “spent every single dime I had” to accept a lowly graduate assistant job. He “slept like two hours a night” in a Maryland apartment that was two hours from campus by bus, subway and another bus. He bought a knock-off Vespa that broke down the third time he used it.

“Oh, the scooter,” sighs Michael Neuberger, then Georgetown’s offensive coordinator. Neuberger tried to fix it, gave up and taxied Barandas for the rest of the year. The two bonded over football, DMV traffic and their mutual love for The Doors.

At Georgetown’s first staff meeting, Barandas says the coaches spoke to him “like they were talking to a child” until the room was stuck on a run scheme issue and he drew up three plays. He was no rube. Among the books on football strategy he’d scavenged was Howard Mudd’s “The View from the O-Line.” He watched an online lecture by former Patriots offensive line coach Dante Scarnecchia. “Couldn’t understand s—,” Barandas says. He rewatched it until he could. Barandas had a stripped-down view of the game that helped the Georgetown staff simplify things, Neuberger says, “especially at nine o’clock at night when we’re banging our heads against the board.”

Former Georgetown assistant coach Maurice Banks reached out to Barandas about joining his staff at Division III Gettysburg College in 2020. By then, Barandas, who’d returned to Rio, was entering his third season as Vasco’s head coach. He’d rebuilt the roster. He’d upgraded the scheme with run-pass options and inside zone runs, even mastering a trademark double-post pass. He’d found a role pioneering a niche sport back home, so he stayed.

“I always felt that my calling was helping develop football in Brazil,” Barandas says.

Pedro Monteiro and his pals ran Arraial do Cabo’s beaches until the ice cream vendors told Monteiro’s parents their kid was cutting into their livelihoods. He was 9. So Monteiro sold comic books, coffee, juice and water at Rio’s bus stops. He sold sandwiches during school breaks. He staged magic shows and charged kids entry. They first showed up without money, so Monteiro called their folks to ensure they brought cash the next time.

“And I sucked,” he says.

Monteiro charged $10 for car washes during his mother’s medical sabbatical at Harvard University. He was 16. It was 1991. The Boston Garden charged little for obstructed-view seats at Celtics games. Monteiro persuaded a police officer to let him sit on the floor. There’s Larry Bird. There’s Michael Jordan.

Monteiro swam for Kenyon College and earned a bronze in the 2003 Pan American Games. As CEO of Effect Sport, his upstart Rio-based sports marketing agency, Monteiro brokered a 36-kilometer swim as its first nationally televised event. But it was his interest in basketball that’d help him sell the NFL on playing in Brazil.

In 2015, Monteiro attended a conference in Portland, Ore., and had two weeks to kill before the NBA All-Star Game in New York. He emailed someone who knew someone who sold him and a friend two fourth-row tickets to Super Bowl XLIX in the end zone opposite Malcolm Butler’s game-winning pick for the Patriots.

“I’ve been to World Cup finals, different events, but, I mean, that was just mesmerizing,” Monteiro says. “Leaving the game, I was like, ‘Hey, we must work with these guys.’”

Free, daily NFL updates direct to your inbox.

Free, daily NFL updates direct to your inbox.

A U.S. Olympic Committee contact connected Monteiro with Mark Waller, then the NFL’s overseer of the league’s international growth. Waller and other league staffers visited Monteiro in Brazil. They explored holding the 2017 Pro Bowl in Rio and even met with then-governor Luiz Fernando de Souza. Brazil’s economy was experiencing a national recession, making it financially impossible for the state to support such an event, but the NFL retained Effect Sport to cultivate the country’s fan base.

Super Bowl LVI in February 2022 was the watershed moment. Monteiro negotiated a media rights deal with one of the country’s four main networks within two weeks of the game. The NFL hadn’t been on a free-to-air Brazilian network in over 20 years. Movie theater managers (like Thiago Souza in Curitiba) showed the live broadcast in their cinemas.

According to Máquina do Esporte, an average of nearly 360,000 people watched at least 15 uninterrupted minutes of Rams–Bengals on RedeTV — modest metrics for networks who’d prefer millions. But within the context of a sudden broadcast of a niche sport, there was a more promising return: 13 advertisers bought commercials, demonstrating a desire for future association with the NFL brand. In August 2022, RedeTV signed a three-year contract to broadcast regular-season games, the playoffs and the Super Bowl.

Pires, Sao Paulo’s 32-year-old tourism head, watched at least five NFL games per week in 2023. He even attempted one game at running back for the SPFL’s Corinthians Steamrollers — “Zero talent, all effort,” he says.

Pires knew any legitimate impact depended on Brazil hosting an NFL event. Effect Sport set up an online meeting between the league and Sao Paulo’s tourism agency in 2022. Pires told them the city wanted to host a game as early as 2023. The NFL remained committed to London and Frankfurt in 2023, but a contingent of league officials reassured Pires that Brazil was a future target. From then on, Pires says he emailed the NFL every 15 days while Effect Sport continued to secure corporate sponsors that signed on without any guarantee of a game.

In August 2023, NFL officials called Monteiro. Estadio Azteca was under renovation for the 2026 World Cup, which had already forced the NFL to cancel its 2023 game in Mexico City. Construction would take longer. The league needed a new international host in 2024. Its targets: Barcelona, Madrid, Rio, Sao Paulo.

Arena Corinthians, home of “the people’s team,” has a capacity of just under 50,000. (Brooks Kubena / The Athletic)

Over the next five months, Pires ran point for Sao Paulo’s proposal. He chose Arena Corinthians (for its field size and parking lot), secured $5 million in financial support from Mayor Ricardo Nunes (the city’s revenue had more than doubled since the recession) and led the presentation with the league in London.

Ten days before the NFL announced the news, Pires got a 9 p.m. phone call in his office. It was Effect Sport telling him Sao Paulo had won the bid. “If it wasn’t for Gustavo, and the mayor trusting Gustavo, it’s very likely the game wouldn’t have come,” Monteiro says.

The league strategically scheduled the game to stand alone on a Friday night in prime time, and it’s blasting the live broadcast through three distinct mediums: RedeTV, easily accessible free-to-air; ESPN Brazil, the league’s longtime pay TV partner; and CazéTV, owned by Brazilian streamer Casimiro Miguel, who has 32.3 million combined social media subscribers, a “big chunk” of private equity from XP, Lopez says, and also landed broadcast rights for the 2024 Olympics.

There’s a unique digital pathway in Brazil. The country has more smartphones than inhabitants, according to a survey by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, and 92.5 percent of households used the internet in 2023. Free-to-air television and radio access dropped by half a million homes since the previous year, and only 42.1 percent paid for video streaming services. But free cell phone apps like WhatsApp connect people from Amazon villages to Rio beaches. On Monday, the Brazilian Supreme Court upheld a decision to block the social network X across the country in an attempt to remove hate speech and attacks on democracy online.

One game per year — or two games, as Pires hopes — may not be enough to burst the bubble, says ESPN Brazil commentator Antony Curti. Indeed, the NFL may not have its desired reach until Brazil’s largest network, TV Globo, takes interest (RedeTV’s deal expires after this season).

But Brazilians “love idols,” Curti says. Formula One wasn’t beloved until Emerson Fittipaldi, Nelson Piquet and Ayrton Senna won championships. Anderson Silva held the UFC title for a record 2,457 days. Rayssa Leal popularized skateboarding by medaling in both the Tokyo and Paris Olympic Games. Brazil needs an NFL idol, Curti says, and it can really only be one position.

“It has to be the quarterback.”

This view was once only hills. Then the Portuguese arrived, planting coffee beans, sugar cane, cotton. Ranches rose. So did housing for servants: some slave, some free. Sao Paulo swelled from the southwest. Industry pushed the ranchers east. The poor built charretes (horse-drawn carts) for the rich. The rich fled, leaving the undocumented poor with only the hills on which to build these ramshackle homes.

“It’s Vila Progresso,” the quarterback says, leaning against the balcony. “Or Progress Village. And there’s no progress in here. You can see that.”

Jorge Ribeiro, 24, was born within this panorama of brick, mortar and corrugated metal. His father sold washing machines. His mother worked reception at a bridal store. Both jobs were downtown. They’d wake Jorge and his younger brother João at 4:30 a.m. and together take an hour-long subway into the city. That’s where the better public schools were, his mother believed, where her sons could safely stay while she and their father secured rent money, food and savings to someday escape the favelas.

That’s one version of life here. Another feeds on the misery. Drug dealers and thieves solicit largely unpoliced streets. Still, the poor build their shanties. If a resident stays on a lot for five years it’s theirs by law. Government installations provide power lines, paved roads and plumbing but little else. The “river” in a nearby ditch overflows with sewage in storms. But Jorge and João didn’t know any better. Nor did they care. For a day, they had a pool.

Ribeiro has only seen politicians (and their camera crews) during elections. Vila Progresso spends the rest of the year mostly forgotten, its families groping for progress, some paying monthly rent to landlords who charge nowhere less than 1,000 reais.

“They have two shitty jobs so they can have one shitty life,” Ribeiro says.

On Ribeiro’s 10th birthday, his mother gifted him a composite leather football she’d bought in a downtown store. He gripped it greedily, threw it and blew out a lamp. “This has been my life ever since,” he says. He nuzzled the ball at night, crying, dreaming of playing in the States. He carried it around school. Classmates stared. You want me to teach you how to throw? He converted few disciples. “Everybody knew me for the weird ball,” he says.

There were worse ways to be known. Saturday nights in the favelas signal the Baile Funk, weekly bacchanals of drugs, sex and gunplay. Tourists wander in as thrillseekers, Ribeiro says, failing to understand the resignation required to rage with abandon, why cops criminalize these parties and fire smoke bombs into the raucous rhythm, why one flirtatious word to the wrong woman can ignite gunshots that leave five wounded and five dead. They fail to understand why playing the lottery for the night of your life or the night of your death is still worth it.

Because when you’re Black, Ribeiro says, there’s no escape. He and a friend were walking one night when a police officer stopped them on the street and drew his gun. Let’s have a ride. Two hours later, the truck stopped. The cop beat them, Riberio says, and had them kneel in the dirt. “He said, ‘I should kill you guys,’” Ribeiro says. “And then we said nothing. And then he told us to stand up and start running. And then we started running and he gave two shots to the air.”

Better to be known as “the football guy, not the Black guy,” Ribeiro says. It’s how he learned English. He searched for random Facebook users with the surname “Smith” and messaged the ones who liked NFL pages. Can I be your friend? I’m going to the United States sometime soon, and I want to be ready. Sure, some Smiths said. Silence, others.

It’s how he first went to America. In 2021, Luiz Ferreira, the former placekicker for the SPFL’s Palmeiras Locomotives, was playing for Presentation College and helped Ribeiro secure a scholarship with the NAIA program in Aberdeen, South Dakota.

But it’s been three years, and Ribeiro remains in Brazil.

Jorge Ribeiro operates “The Chosen One” QB academy close to where he grew up in Sao Paulo’s favelas. (Brooks Kubena / The Athletic)

His father’s cancer first brought him back. His mother and brother, who has mild Down syndrome, couldn’t handle it alone. After his father recovered, Presentation College shuttered due to lack of funding. Ribeiro landed a partial academic scholarship at Rockford University, a Division III school near Chicago. Its student services office connected Ribeiro with a Brazilian benefactor who paid the remaining $11,000 balance. “You’re a warrior,” the benefactor told him.

Ribeiro wears a brace knowing that statement’s still true. After spring practice sprints in 2023, Ribeiro says his cleat slipped in muddy grass. His knee dislocated. His ACL popped. A Rockford spokesperson confirmed Ribeiro was enrolled but denied he was on the football team. Ribeiro says his benefactor fell out of touch after the surgery. “I mean, he’s a businessman,” Ribeiro shrugs.

Ribeiro blamed God for his return to Brazil. But after two months, his girlfriend Jani grabbed him by the shirt. Wake up! Move on! We’re going to find our way back! They married, had a daughter and moved into a gated apartment 20 minutes from Vila Progresso.

Small progress. Ribeiro has two jobs and one hopeful life. He sold his football helmet to buy an iPhone 13 and a data plan. He needed the camera to create content after starting his private quarterback training academy, “The Chosen One.” He charges seven pupils 40 reais per session. It’s next to nothing, he knows. But how else can the sport advance?

How long might that process take? A decade? Ribeiro, who wants to raise his daughter in America, doesn’t intend to stay in Brazil that long. But for now, he says, he must share his knowledge. He must build people up within these hills.

“It’s like a preacher, I guess,” Ribeiro says. “I’m telling people the good way to go.”

A entrada é por aqui!

The beer carts are empty. The tents are folded. The last-minute line of Corinthians fans crams into one of the arena’s gates.

There’s a reason the Brazilian motto “Ordem e Progresso” (“Order and Progress”) is often spoken in jest. An overtly bureaucratic system that requires its citizens to use their equivalent of a social security number to buy soccer tickets sometimes forgoes order for process.

The line clogs. A man takes offense to a steward’s insistence that he must enter a different turnstile even though they all lead to the same hallway. Shoving. Screaming. An officer drives the man out with a baton.

In the stands, voices boom by the thousands. The stairways divide a crowd dressed in black and white. Beneath one awning of the open-air canopy is painted Time Do Povo, “the people’s team,” signifying the club’s connection to Sao Paulo’s working class.

As Friday’s designated home team, the Eagles aim to endear with their black-and-white alternate ensembles. Corinthians wears black and white. Archrival Palmeiras wears green. A state law, “Torcida Única,” cuts down hooliganism by banning away fans — often identified by what color they wear — from attending games between the city’s rival soccer clubs. This rule does not apply to the NFL, whose traveling fans can freely wear whatever they’d like. Jon Ferrari, who partly oversaw international operations as Philadelphia’s assistant general manager, said the Eagles chose black as “a unique nod” to the Corinthians fanbase. The Packers are wearing their standard home green uniform.

GO DEEPER

Jason Kelce and Philadelphia, center and city, a perfect fit entering a new era

Both Arena Corinthians and Arena Palmeiras are impressively modern stadiums. The pre-game scenes are as festive as college football tailgates. Fans gulp beer, scarf down sanduíches de pernil and bellow for hours. A city with New York’s sense of size with a South Florida ambiance is hungry to consume an elite American match — and hopes it’s not the only one.

The NFL intends to return. “The vision is not a one-and-done,” Peter O’Reilly, the league’s head of international affairs, said. Through a Brazilian research institute (IBOPE), the NFL saw the number of Brazilians “interested” in the league spike from 3 million in 2014 to 38 million in 2023. Beginning with Eagles-Packers, the NFL aims to convert that surge into more “avid” fans — those who watch games regularly, buy league products, attend events — a number the institute pegs in Brazil at 8.3 million.

“This is about a game as a catalyst to deeper, year-round engagement,” O’Reilly said.

Can the NFL maintain its momentum? Some have already decided the costs are too high. Arthur Lipsi and his friend Felipe Mengoni, both 18, spent eight hours in the box office line but retreated empty-handed when the only seats remaining were 1,700 reais each ($302). Dirceu Bertin, 66, bailed when the designated line for seniors got too long. Elvis Vasconcelos, a carpenter, considered the cost of losing a potential work day but still paid 1,650 reais for one ticket.

“I need to work, like, hard,” Vasconcelos insisted. “But today is a special day.”

(Illustration: Dan Golfarb / The Athletic; photos: Brooks Kubena / The Athletic)