Dr. Rajinikanth and his wife Dr. Padma would regularly play chess together for fun at their family home in India. Always at their side, watching wide-eyed, observing intensely as each piece was strategically moved on the board, was their son, Gukesh. The young boy was captivated by the calculated black and white dance before him.

“He would become fascinated with how the pieces worked,” Rajini tells The Athletic.

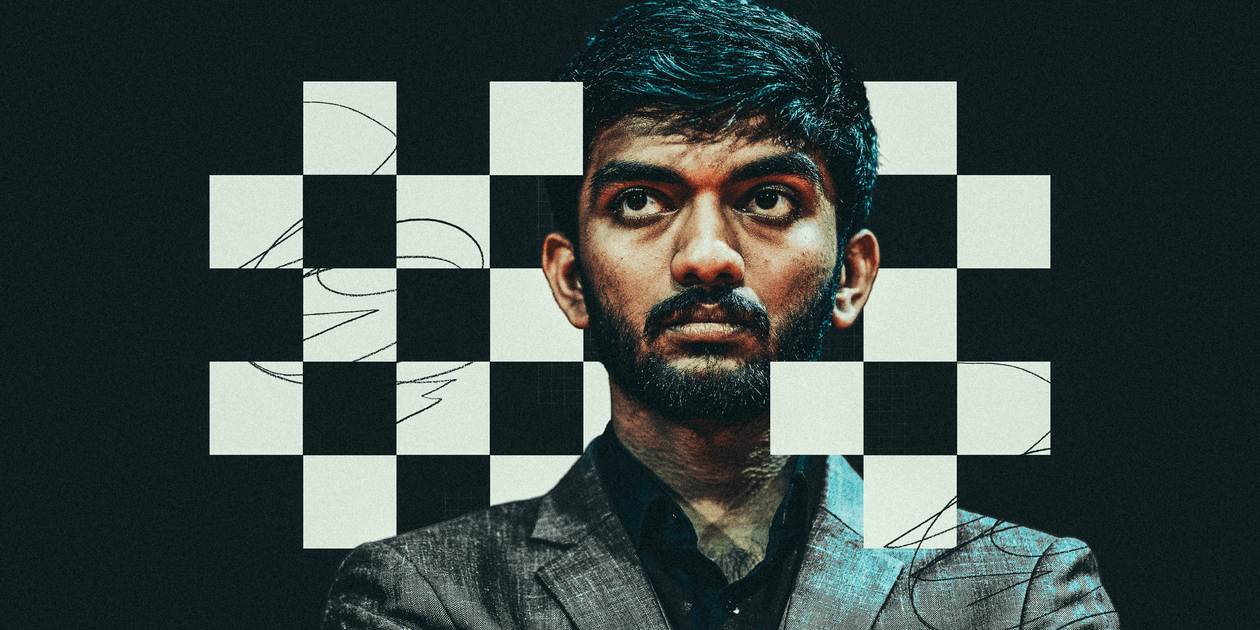

Over the next few weeks, Gukesh, still fresh into adulthood, could become the youngest-ever chess world champion. By qualifying for this month’s 2024 World Chess Championship in Singapore, the 18-year-old is already the youngest challenger to compete for the world title.

It has been a meteoric and surprising rise for a player who, until the summer of 2022, was still solely ranked as a junior. “It just happened by accident,” says Rajini, a surgeon. His son’s success wasn’t preordained, he says. Neither he nor his spouse, who is a microbiologist, had planned for or dreamed of their son becoming a phenomenon in the sport. “We never realized he was a special talent,” he explains. “It was the schools, teachers, and coaches who started to tell us, ‘This kid is talented, you should pursue more’.”

Starting on Monday, Gukesh will play titleholder Ding Liren, 32, of China in the best-of-14 classical games match that could last until December 13. For the first time in 138 years, two players from Asia will contest the final.

Gukesh, from the city of Chennai on the Indian south coast, a hotbed for chess talent, won the eight-player 2024 Candidates tournament in Toronto to set up the chance to become the first teenager to win the world title. Aged 17, in his first appearance at what is essentially the final round of World Championship qualifying, he overcame the odds and got the better of five more celebrated players — all with higher rankings — earning his title shot with five wins, one loss, and eight draws to finish with a score of nine out of 14 (one point for a win, half a point for a draw, and zero for a loss). Should he triumph in Singapore, he will become India’s second world chess champion after Viswanathan Anand.

Ding competes against Gukesh during the Tata Steel Chess Tournament in the Netherlands in January 2023. (Photo by Sylvia Lederer/Xinhua via Getty Images)

Perhaps such success shouldn’t have been surprising given the records he broke as a child. Still young enough to be included in the International Chess Federation’s (FIDE) junior world rankings, he is the world’s top-ranked junior male player in classical chess, the longest format of the sport.

That he could beat the defending champion isn’t in the realm of fantasy, either. Gukesh, ranked fifth in the world in this month’s classical rankings, is the in-form player. Ding, currently 23rd, has had a difficult reign as world champion, taking a nine-month break from the sport last year for mental health reasons. He hasn’t won a classical game since January and has only played 44 classical games since becoming world champion.

“I am worried about losing very badly. Hopefully it won’t happen,” Ding said to chess app TakeTakeTake in September. At this week’s press conference, Ding said he wasn’t at his peak but said he was at “peace” and would review his previous best performances for inspiration.

Ding does, however, hold the better record in the pair’s head-to-head classical meetings, winning two and drawing once, and his peak FIDE rating of 2,816 is higher than Gukesh’s (2,794, reached in October).

But Magnus Carlsen, the five-time world champion who opted not to defend his world crown in 2023 but is still ranked as the world’s best classical player, has backed Gukesh to win, and urged the importance of Ding making a fast start.

“Ding cannot lose the first game… from what we’ve seen from Ding for the last one-and-a-half years, I don’t think he’ll come back from losing the first game, so I agree, hesitantly, that he’s going to be the first person to win a game, but I’m very uncertain,” he told chess.com. The Norwegian added: “The only way there’s going to be a low number of decisive games is that Ding gets chances and keeps missing them. We could see a bloodbath.”

‘Gukesh D’ as he is known, started playing chess at the age of seven, winning various junior tournaments before becoming, at the time, the second-youngest grandmaster, aged 12 years, seven months and 17 days. Grandmaster, awarded to players by governing body FIDE for life, is the highest title outside of world champion; today there are more than 1,850.

This year, he became the third-youngest to reach a FIDE rating of 2,700 after claiming two gold medals at the Chess Olympiad — a biennial international tournament that was held in Budapest, Hungary, and he is the youngest player to achieve a rating of 2,750.

Gukesh said his youth could be viewed as a negative and a positive heading into the final, but at this week’s press conference Ding said his opponent played with maturity “in many aspects”. Known for being an aggressive player, Gukesh, who recently revealed he was a fan of the sitcom Friends, is one of a number of young players making a name for himself in the sport. Ding recently decribed the new generation of players as fearless. “There are a lot born after 2000, they play fearlessly and are willing to try different strategies that the previous generation might not have,” he said, according to The Straits Times.

Gukesh is welcomed at Chennai International Airport after winning two gold medals at the FIDE Chess Olympiad (Photo by R. Satish Babu/AFP via Getty)

One of the coaches who told Gukesh’s parents about their son’s special ability and helped his development was Indian grandmaster Vishnu Prasanna, who coached the prodigy from 2017 to 2023.

They first met after Vishnu hosted a small training camp for students from Gukesh’s school, Velammal Vidyalaya, which has a great reputation for producing chess talents. Developing a strong mentality was a big focus point for Vishnu. “We discussed a lot of non-chess stuff about mindsets and how people in extreme sports behave,” Vishnu tells The Athletic.

“We talked a lot about Alex Honnold (the American free solo climber) and many extreme athletes and what kind of mindsets they try to keep. I always emphasized that chess techniques come and go and can be played around with, so there is no one right technique. But there can be a right mindset that promises performance, and that is the difference between players rather than the chess itself.”

His parents never involved themselves in training, instead making sure life outside of the sport was settled. But, with the approval of Gukesh’s parents, Vishnu, experimenting with his approaches, resisted the use of computer or chess engine assistance until Gukesh was a grandmaster, the aim being to encourage Gukesh to think on his own.

Chess had a deeper impact, too, on the teenager. “He used to be very naughty,” says Rajini.

“He was the only child so whatever he wanted he had to get it sometimes. He used to have all these tantrums but once he started chess he became very observant, how he is now. He started becoming more calm, patient, and observant. Chess has changed him.”

Playing chess can cause mental fatigue because of the concentration required. Yet, Gukesh’s appetite for the game once saw him play 276 games in 30 tournaments across 13 countries over 16 months while squeezing in 10am-5pm sessions with Vishnu in between competitions.

The longest game at a World Chess Championship was in 2021 between Carlsen and Ian Nepomniachtchi, taking seven hours and 45 minutes. Such mental focus can take its toll. After the ‘Moscow Marathon’, a World Championship contest between Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov that lasted five months and 48 games, Karpov told a Russian magazine he had lost 10kg (22lb) in weight.

Gukesh could become the first Indian world champion since Viswanathan Anand (Photo by Marcus Brandt/picture alliance via Getty Images)

In Singapore, each classical game will follow the time control of 120 minutes for the first 40 moves, followed by 30 minutes for the rest of the game. From move 41, a 30-second increment will start. Players must remain poised, balanced and consider their moves deeply. A score of 7.5 points or more will win the world title. If the players are level after 14 classical games, a tie-break will be played on December 13. The right mindset is paramount, says Vishnu.

“It’s probably the biggest stage that anyone would get to, it’s all about nerves when you get there,” he says.

“He has been thriving under pressure. So far, he has always delivered in moments where he has a lot to lose and when things are hanging by a thread.”

History is on the line, and so too is a lot of money. The total prize pot for the World Championship is $2.5million, with each player earning $200,000 for each game they win. The remaining prize money will be split equally between the players. This is a significant hike from the €48,000 ($50,489 at current currency conversion) Gukesh banked from winning the Challenger tournament.

Even if Gukesh remains calm under the Singapore spotlight, his parents will not be relaxed. Padma does not watch her son’s matches because the experience is too stressful. Instead, she will wait for the results to come in.

“I also want to do that, because it is too stressful for us, but it is too difficult to stay away so it’s like a hide-and-seek. So I just watch once every half an hour or hour and just see what position he is in,” says Rajini.

Tournaments have taken Gukesh, accompanied by his father, all over the world. There have been sacrifices, but the family have few regrets.

“Two-thirds of the year we were travelling for tournaments — his mother got very little time to spend with us. That is one thing we regret. Otherwise, we are very happy with how things turned out and we are very fortunate,” says Rajini.

Coach Vishnu saw the pursuit of greatness first-hand. “There is no clear path to recreate what he has done,” he says. “A certain hyper-focus and sacrifice of a regular childhood, a regular school life, and a regular social life of a teenager, you give up all that and focus on the main thing and that is to get better at chess.”

There are increasingly more chess prodigies, but Gukesh has worked persistently to fulfil his potential. “I had no doubt he was going to do well but, still, he exceeded expectations,” says Vishnu.

Gukesh is following in the footsteps of a great: five-time world champion Anand, now the deputy president of FIDE and also from Chennai. Fittingly, Gukesh overtook him in the chess rankings last year to knock him off the top spot as India’s highest-ranked player, a position he had held for 37 years (although Arjun Erigaisi, in fourth place, currently holds that honour).

Anand dominated an era, including winning four consecutive World Championships between 2007 and 2012.

“Playing the world championship and winning the Candidates is trying to fill Anand’s shoes, which is something my generation tried but failed to do,” says Vishnu, 35.

“So it is very inspiring that Gukesh is close to putting India back on top of world chess, looking back and thinking, ‘That was the kid who was coming and training with me’.”

(Top image: Andrzej Iwanczuk/NurPhoto via Getty Images; design Eamonn Dalton)