NORTON SHORES, Mich. — There is nothing outside that suggests the machines sitting inside this gray, nondescript building in an industrial office center could disrupt the trading card industry.

Sign your name on the clipboard just past the entrance. Walk by a long table with pizza boxes next to a refrigerator and it all feels pretty normal. It’s not until you turn the corner and see millions of dollars worth of machinery in an open space flanked by a giant American flag on the wall that it starts to feel different. When you’re asked not to take certain pictures or video because of the required privacy of inventory nearby, yeah, that’s when everything changes.

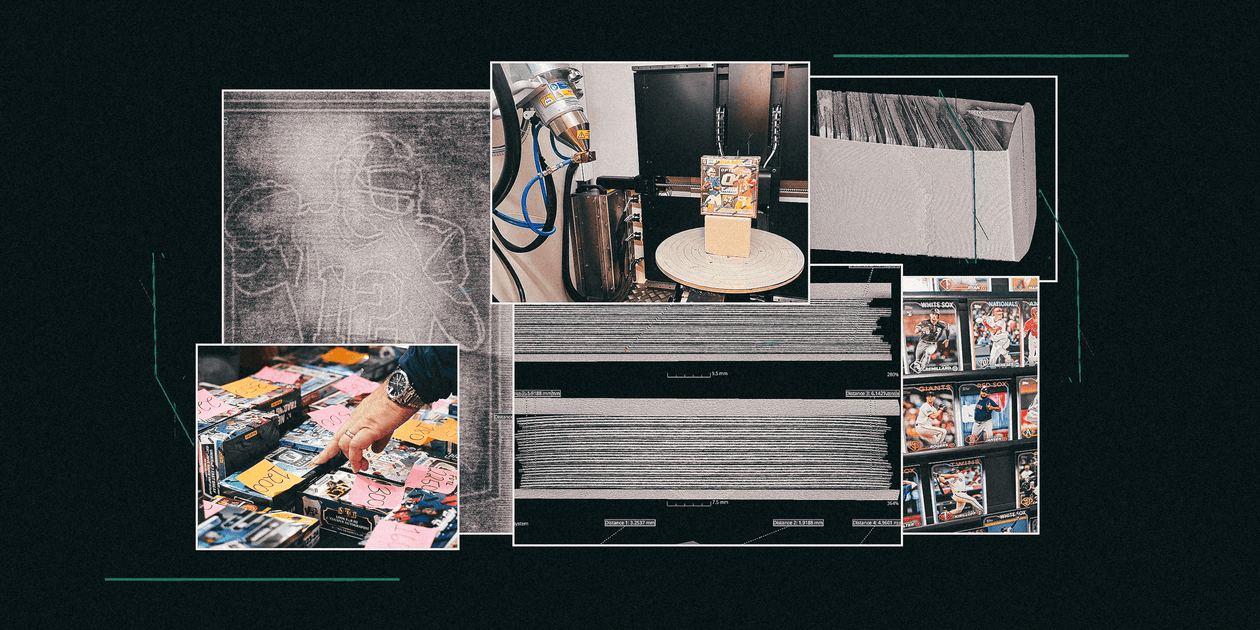

There could be airplane parts. Pieces of a satellite. Rocketry. Military ballistics. And on a recent Friday afternoon, an unopened Mega Box of 2023 Donruss Optic Football cards with Anthony Richardson and Brock Purdy on the front, bought at a Detroit-area Meijer for $60.

The goal? To use the technology at Industrial Inspection and Consulting to see what’s inside without breaking the plastic wrapping that traditionally indicates an unsealed, untouched and unexamined package of cards.

For most of its history, buying and selling packs and boxes of trading cards was a game of chance with neither the buyer nor the seller knowing the results.

“The product is designed to be a mystery,” said Keith Irwin, the general manager of Industrial Inspection and Consulting.

And if it wants to stay that way?

“They’ll need to find new packaging solutions,” he said.

IIC went from a company focusing primarily on industrial X-rays and CT scans within the medical and aerospace fields to potentially taking the cover off the trading card industry without taking the cover off any product at all. And in the process, they say, their company — with no prior connections to the trading card industry — has earned thousands of satisfied customers in the collectibles space. All electing for a sneak peek at their cards before tearing the packs or boxes open, circumventing the mystery that has long been a central element of these products.

The service caters to high-end products manufactured by Topps, Panini and Upper Deck, with the technology best suited to reveal cards in densely packed configurations. Take a 2023 Panini Flawless Football First Off The Line case for instance. Each case comes with two boxes. Each box comes with one pack of 10 cards. At $15,000 a case, it certainly makes economic sense that collectors are willing to pay IIC the going rate of $650 per case of that product to get a CT scan and see whether there’s something inside that they want, or to keep the package sealed and sell it on to someone else.

The economics are easy. But the ethical dilemma isn’t for this group of non-collectors in western Michigan whose industrial scanning start-up has received a financial windfall from those in the hobby willing to pay for a preview.

“We’ve had to wrestle with that as a team and some of us think differently about it,” Irwin said. “So some of us say ‘It is what it is. We can do it (scan products).’ And others say, ‘This feels like we’re participating in something that is very much in a gray area.’ And we still wrestle with it. I think where we land is that we are data people and we’re very good at what we do. And if we’re not doing it, then somebody else will.”

Nick Andrews, co-host of the Sports Card Madness podcast, has been one of the more prevalent online commentators addressing the practice of CT scanning since IIC opened its doors to the trading card industry in late July. He’s been loudly expressing how this could be a significant concern within the hobby.

“I think ultimately they took the stance of Napster in a way, like they’re not committing fraud,” Andrews said. “What these people do with these CT scan(ned) cards is not their problem. You know, they’re not the shepherds or steward of the hobby.”

IIC’s website states, “Pandora’s box is open,” which is an interesting choice of words considering the controversial practice involves not opening the sports card box at all.

“I think that you can probably draw a lot of correlations to different industries that have been negatively impacted by a group or a large number of groups that figure out a way to get an edge,” said Zach Stanley, CEO of WeTheHobby, one of more prominent online card dealers and box breakers (the practice of opening boxes of cards in larger quantities after customers buy the rights to all the cards of specific teams, players, etc. that may come out of them) within the industry. “I also think my hope is that it is something that can be combated from a technological standpoint, but we’re obviously a ways off from that now.”

And with the CT scanning technology comes the increased possibility for questionable resale practices at best and fraud at worst.

“I’d strongly encourage collectors to buy from established shops they trust,” said Eric Doty, CEO of Loupe, a live streaming platform for online vendors. “The short-term gain you’d make from scanning is not worth the risk of losing your entire business due to breaching that trust.”

Stanley said WeTheHobby has been approached by other contacts within the industry to explore or be helped to explore CT scanning technology. He immediately followed up saying, “Obviously we rejected (the offer) quickly.” But not every seller stands on equal ground, or possesses an equal moral compass.

“When people get desperate they do desperate things,” Stanley said.

A 2000 Bowman Chrome Tom Brady rookie card as seen through the CT scanner. (Image provided by Industrial Inspection and Consulting)

It all began over lunch and a search for Charizard. The start-up industrial scanning company was looking for ways to market its capabilities and a brainstorming session led to the idea of scanning packs of Pokemon cards. Compared to airplane parts, scanning packs of cards was child’s play.

“It was like a revelation of ‘Holy cow! Not only did this work, but it’s extremely obvious,’” Irwin said. “That was really the extent of what we thought. So hey, let’s throw it up as a case study.”

Irwin said he posted the imagery and results on his LinkedIn page in late June, where it received “140 or 150 likes and tons of comments.” The company had no idea what it stumbled upon.

“Immediately we were like well nobody’s gonna be paying for our labor to be able to do this,” Irwin said. “But I think that that was a naive thought because we didn’t understand the true value of these cards.”

The values of sports and Pokemon cards have grown exponentially in recent years, with regular sales in the six-figure range and some going well into the millions (the highest sale to date for a Pokemon card was nearly $5.3 million in 2022 and the highest sale for a sports card was $12.6 million, also in 2022).

Irwin said the company began receiving emails from parties interested in having products scanned following the post on social media. He estimated it only took a week and a half from there to turn it into a “full flooded service.”

“We laugh that you have rocket components sitting on one shelf and then cards on the other shelf,” Irwin said. “It’s just odd.”

Irwin estimated the volume of product IIC has scanned since starting in July to be “in the thousands.” Though that’s still just a drop in the bucket for an industry that produces millions of packages of cards each year.

Now months into what’s gone from lunch room chatter to a sizable portion of Industrial Inspection’s income, what’s the biggest technical challenge for scanning thick paper and cardboard?

“How do we go fast enough to make it worth it for people to pay,” said Irwin, who told The Athletic on Wednesday the company has hired additional full-time staff to help with the card demand.

And what’s become the biggest non-technical challenge entering an unfamiliar niche space?

“It’s a moral dilemma,” Irwin said.

There have been threats. A window near the front of their building is covered. They’ve taken steps to protect themselves from those in the collectibles business who believe what they’re doing is morally wrong and a serious threat to a billion dollar industry.

“I think it’s certainly a disruption (in the industry). … First of all, for boxes that were produced before today, I think as a potential buyer of those boxes you have to be very cautious,” Professional Sports Authentication (PSA) CEO Nat Turner said in a recent interview on the Sports Card Madness podcast. “Basically you have to assume the box has been scanned. So I think you can see a price correction in boxes that are thrown up on eBay, for example, perhaps. But I think manufacturers I think are going to have to respond.”

The CT scanner loaded up with a box of football cards. (Photo: Craig Custance)

There’s been rampant speculation within the hobby long before IIC existed around card vendors using CT scanners to view inside card packs and boxes. Many times online accusations occur when box breakers unveil what some within the hobby would deem a disproportionate amount of “hits” from sealed products with a break.

Irwin said the company has seen verified proof that “many sources” are already scanning products and have been doing so without being public about it. (No proof was offered to The Athletic for this story.) IIC was the first one openly offering the service for certain price points, which is part of its moral defense. It believes it’s being very transparent about all of this. Its price list is on the website. So are pictures of the scans. IIC invited The Athletic in to see how it all works in person, an invitation that was accepted.

The company specifically quotes prices for high-end products (boxes priced around $1,000 or more, generally) manufactured by Topps, Panini, Upper Deck and Pokemon on its website, whose homepage essentially doesn’t promote the service at all other than an initial announcement near the bottom of the page. There’s a focus on cards from the last 25 years or so containing foil, raised portions, imprinted numbering and patches or relics (cards containing pieces of jerseys or other memorabilia) since those elements are the most defined on the scans.

Pricing varies per product. For example, IIC charges $75 for one box of Topps Dynasty, which is one of Topps’ premier products containing only one autographed patch card encased in a plastic holder and carries a retail price anywhere from $900 to $1,200, depending on the sport or year.

“Dynasty is our favorite, I’ll say that,” Irwin said. “It’s probably the easiest to detect, I’m guessing. It’s a single (package), it’s one to two cards, typically one card. It’s just a dream, and those are very expensive products. We sent out a quote to somebody with a Dynasty box, and they’re like, ‘God, this is a no brainer, I’m sending it over.’”

A patch autographed card numbered to 10 of Formula 1 star Max Verstappen from 2022 Topps Dynasty (image below) serves as one of IIC’s prime scanning discoveries. The card displayed by IIC last sold on eBay for nearly $2,200 on Aug. 3 according to CardLadder, which tracks sales across major online marketplaces.

When asked if card manufacturers like Topps and Panini have reached out to discuss the company’s scanning practices, Irwin said, “Any conversations like that are under non-disclosure, but we have spoken with a variety of interested parties that are leading the market. So I’m not just talking manufacturers — auction houses, authentication houses, third-party services that are like couriers, you name it. Pretty much anybody that is interested has either spoken to us or spoken to people that know us.”

Fanatics Collectibles, the owner of Topps, declined an interview for the story. But people inside Fanatics Collectibles told The Athletic: “While we believe that CT scanners aren’t currently being widely utilized, we take any issue that potentially harms collectors very seriously. As such, we are working on innovations and solutions to address the issue.”

Panini declined to be interviewed for this story. Upper Deck said it would look into the possibility, but never agreed to an interview. Goldin Auctions and parent company eBay declined an interview for the story, deferring the issue to individual sellers. The Athletic also reached out to four other prominent online vendors who never responded to interview requests.

When asked if the conversations with other parties involved a request to discontinue scanning products, having products scanned or ways to hinder the ability to reveal the contents of a product through scanning, Irwin said, “All of the above.”

“That’s an interesting question because it seems like publicly everybody wants us to stop,” Irwin said. “In private, nobody wants us to stop because everybody that you can imagine has reached out to us.”

There’s also no way to know whether a pack or box has been scanned without the person or company divulging that. There’s no database kept by IIC for what’s been scanned, nor is there an indicator placed on the product to show it’s been scanned by IIC.

Additionally, the company doesn’t know the true identity of everyone sending in products to be scanned.

“We’re not verifying our clients,” Irwin said. “A lot of them we assume are using fake emails. And so we don’t know who they are. Fake emails, fake names, and then we use Square for credit card processing. So we don’t know who any of these people are, honestly.”

Irwin said the company hasn’t looked into any instances of nefarious practices by individuals, box breakers, hobby shops or anyone else using IIC’s services once a scanned product leaves its hands.

“Our objective position is one of scientific ability and data-driven results,” according to IIC’s website. “It is not our responsibility to determine the ethical positions and choices of others and we do not accept responsibility for their actions. Our quotes require clients to disclose to their potential buyers if they have CT scanned their sealed products.”

The consequences from IIC for a customer failing to disclose to a potential buyer that a product was scanned is unclear. Legally speaking, that’s a different story.

Paul Lesko, a Missouri-based attorney known for being “The Hobby Lawyer,” said while scanning packs and boxes may be legal, consumer fraud charges could result for the owner of scanned products if resold without disclosure.

“Consumer fraud claims require a knowingly false representation about a product made with the intent for buyers to rely on that misrepresentation,” Lesko said. “So, if a seller scans a pack/box and determines it does not have a hit (industry parlance for a desirable/valuable card), but when selling states it ‘could contain an auto(graph) or patch’ or really just recites that the boxes ‘may contain an auto or relic’ or just shows a picture of the box with that representation from the manufacturer, that’s a false representation made by the seller in the hopes of duping the buyer.

“Best case scenario, after scanning a pack/box, if you’re going to resell it, disclose you scanned it.”

Irwin posed the question that anyone in the hobby would ask, though.

“Are people going to do that? I have no idea,” Irwin said.

Irwin was handed the box of 2023 Donruss Optic football cards, our attempt to see just how effective his technology was and the first thing he did was turn to YouTube. He wanted to learn more about a product in which he was unfamiliar since most people weren’t spending $75 to scan a $60 box of cards.

He landed on a video of a breaker sorting through each card individually. Immediately, he was able to determine that his machines wouldn’t be able to pick up the names of each player on the cards because of the design. But he was confident in the ability to pick up the outline of the players along with any uniform numbers, important indicators when searching for specific hits. He also expressed confidence in the ability to identify numbered cards and patches.

So we moved on to the next step.

A few feet away, a giant XTH 320 X-ray machine sat, waiting to reveal what was inside this box of football cards. Irwin placed the box in the middle of the machine on a round table on top of a piece of styrofoam. A large sliding door closed slowly, sealing itself next to a red emergency stop button and a caution sticker. Within minutes, the contents of the box of cards showed up on a monitor near the machine, each card a blurry gray rectangular shape that revealed little, until the outline of a patch on one of the cards became clear.

About 20 minutes later, the CT scan was complete. Irwin was able to rotate the scan in every direction. He was able to zoom in on specific cards. It was abundantly clear that the bottom pack contained the patch card, which he was then able to rotate and zoom in on to identify more characteristics of the card.

If we knew the specifics of a card we were trying to get, at that point we would have been able to identify it. But in the case of this patch card, we only could make out vague details. There was some writing on the front. It appeared to be a wide receiver with a number in the 80s. Just as important was identifying what wasn’t in the box. There didn’t appear to be any numbered cards. If we wanted to spend the time, we likely would have been able to determine there wasn’t a C.J. Stroud.

Once opened, the patch card turned out to be Raiders tight end Michael Mayer. A 10-minute scan of the contents was enough to conclude this wasn’t a particularly valuable box, which ended up being confirmed when it was later opened the old-fashioned way. By a 13-year-old ripping through foil.

The Michael Mayer patch card detected by the scan. (Photo: Craig Custance)

It wasn’t a fast process. There was a lot of card rotating and data reading. To truly benefit, there needs to be a target card in which the person doing the scanning can be on the lookout for. It’s tedious work on expensive equipment, one reason Irwin isn’t convinced the work is going to spread throughout the industry.

“You saw me scrolling through this data, it’s annoying, right?” Irwin said. “We were a startup hungry for work. We’re all workaholics without enough work. So we stumble upon this thing that nobody’s done before and all of a sudden we have… clients in a brand new territory.”

It’s transformed his business. Whether it alters another just might depend on what happens next.

There is a train that runs past the industrial complex where these scans are taking place, blaring its horn each morning while crossing a nearby road. It’s close enough that the shaking it produces in the building can disrupt scans that rely on complete stability for pinpoint accuracy.

The slightest vibration can get in the way of an accurate scan and that realization has helped this same group design a solution. IIC has patented a process that would make the scanning much more challenging.

“All (new packaging) has to do is introduce a slight vibration to the cards and it makes it very challenging for us to read it,” Irwin said.

The company hopes its solution would either be licensed or outright purchased by a card company.

“It would be strange to both want to be the fixer and then also the breaker,” Irwin said. “But in the conversations we’ve had, we’ve been compared to say Google wanting to hire the hacker to go through their systems, find loopholes, find ways in.”

But that still leaves every unopened product in the world made up to that point unprotected.

Geoff Wilson, a prominent YouTuber and owner of Cards HQ in Georgia, said in a video posted last week that he believes the CT scanning topic is an overblown issue for most collectors. He immediately followed up, though, saying certain types of collectors and investors should be “terrified.”

Wilson pointed to high-end sealed wax boxes that people have held onto for years as being an issue. He went so far to say he’s in the process of selling off older sealed boxes he’ s collected because “people will forever be concerned that this box was CT scanned” and the concern will only grow over time.

“I mean because of the moral gray, I think the best thing to do would be to eventually find a way to stop this, move out of it,” Irwin said. “What does that do for the last 25 years of product that is prime for CT scanning? I don’t know.”

So there lies the dilemma for the industry. The biggest problem isn’t that this is happening on a small scale. It’s that it’s creating distrust amongst consumers on a potentially larger one.

“Once you sow that distrust with the consumer, you’ve got bigger problems,” Stanley said. “I think that right now, educating the consumers on the fact that this is happening is going to enable them to be educated and prioritize who they are buying from. I think the resale market right now for sealed wax is going to become increasingly problematic.”

Follow The Athletic’s regular, in-depth sports memorabilia and collectibles coverage here.

The Athletic maintains full editorial independence in all our coverage. When you click or make purchases through our links, we may earn a commission.

(Top image: Industrial Inspection and Consulting, Craig Custance, Bruce Bennett/Getty Images, Mark Cunningham/MLB Photos via Getty Images; Design: Meech Robinson)