TYSONS, Va. — Byron Leftwich slips into the Northern Virginia brunch spot unrecognized and unbothered.

Lean and broad-shouldered at 6-foot-5, the former NFL quarterback looks like he could still play even though his 45th birthday looms in a couple of weeks. After a nine-year playing career, Leftwich made a meteoric rise up the coaching ranks. As offensive coordinator of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, he helped Tom Brady and Bruce Arians on a storybook Super Bowl march to cap the 2020 season. Leftwich was a legitimate head coaching candidate in the winter of 2022.

But time moves quickly, circumstances change and memories fade. So on this chilly morning in the middle of football season, Leftwich is just another guy lost in the hustle and bustle of the DMV.

He has spent the last two football seasons largely shrouded in mystery — once a virtual lock to lead his own team, then fired, then off the grid. And thanks to his relatively solitary nature, Leftwich’s goals and whereabouts have remained murky.

Influential NFL figures tried to maintain contact with Leftwich to keep him on the radar, but they say their messages and calls went unanswered. Former colleagues relayed conflicting accounts: Some said he was on shortlists for a handful of college jobs; others reported he had largely isolated himself in West Virginia while waiting for an NFL offensive coordinator role to open up; others sensed Leftwich no longer wanted to coach.

Leftwich is here to clear that up.

“I. Want. To. Coach,” he says emphatically over what’s left of his fried eggs, bacon and a biscuit.

After a year-and-a-half devoted largely to his 14-year-old son, Dominic — making breakfast, dropping off and picking up, traveling up and down the East Coast for a demanding AAU basketball circuit, watching every football practice and game — Leftwich wants back in the coaching game.

“There’s something missing. … I really do feel as though something’s not there, and I’ve got to get back to it,” says Leftwich, who received his son’s blessing to return. “I’m really into helping other players. I want to help them to play the best. I love to teach.”

Leftwich viewed his sabbatical as an exercise in patience. After things ended in Tampa, he promised himself he wouldn’t pounce on any opportunity for the sake of landing a gig. He didn’t direct members of his small circle to drum up a media campaign to keep his name hot and wasn’t about to ask counterparts for handouts. Confident in his body of work, Leftwich maintained a belief that at the right time, the right job would present itself.

Two hiring cycles quietly came and went, but Leftwich has remained unshaken.

“I didn’t have the opportunities right after and this last year that I thought I would have, but I understand the process, and I understand that the whole world’s trying to get in that league,” Leftwich says. “Nothing should be given to me. Nobody owes me anything. So, I’m going to just work and see if I can have the opportunity to coach in that league again.”

Some league insiders believe Leftwich’s under-the-radar approach may have cost him. But it’s the route he feels most comfortable with, even if his supporters wish he were more outspoken.

“Byron will not push himself out there. He’s going to do it on his work,” says Arians, Leftwich’s offensive coordinator in Pittsburgh and coaching mentor in Arizona and Tampa Bay. “But I’ll say it: I think it’s total bullsh– that he’s not a head coach in this league.”

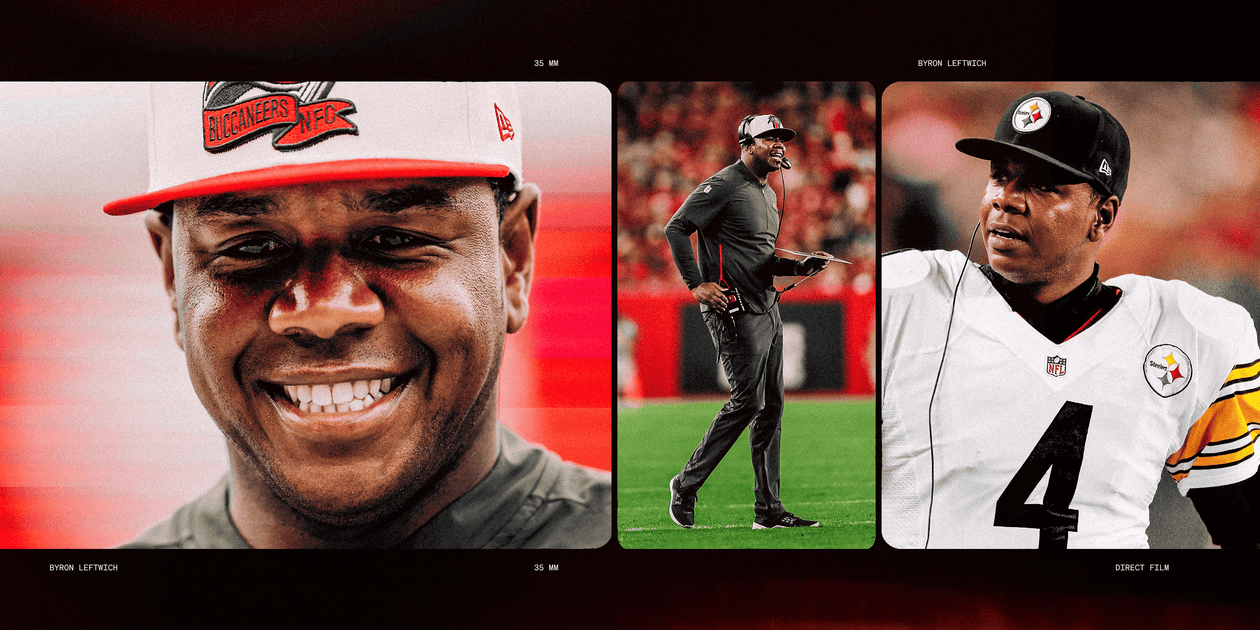

Tom Brady and Byron Leftwich racked up 31 regular-season wins and one Super Bowl run in three years together in Tampa. (Maddie Meyer / Getty Images)

Arians can’t talk about Leftwich without recalling the November 2002 game in which Leftwich, in his final season at Marshall University, played the fourth quarter with a broken left tibia. Leftwich was unable to walk, but his offensive linemen carried him downfield between pass completions as the quarterback racked up more than 300 passing yards.

They began working together eight years later when Arians was the OC in Pittsburgh at the end of Leftwich’s playing career. The coach recognized that Leftwich, then backing up Ben Roethlisberger, was among the strongest leaders on the team. Arians became convinced Leftwich would become a strong coach.

“He’s the toughest and one of the smartest, brightest dudes I know,” Arians says. “He was such a bright quarterback, and he had a great rapport with young players. … Guys have questions, he could answer anything and everything: Why and how it’s going to make you better if you do it this way. He just has a great feel for the game.”

“Awesome leadership qualities have always oozed out of him,” Steelers coach Mike Tomlin says. “Some of it comes from the position he played, but he has always had an ease about him when it comes to leadership. He’s comfortable in his own skin and gets along well with people, and he carries himself in a way that commands respect.”

Arians hired Leftwich as a coaching intern with the Cardinals in 2016. A year later, Leftwich was promoted to quarterbacks coach in Arians’ final season in Arizona. A year after that, Leftwich served as interim offensive coordinator for the final nine games of the season before being let go with the rest of Steve Wilks’ staff.

In 2019, Leftwich was reunited with Arians in Tampa Bay. He largely flew under the radar his first season as a full-time offensive coordinator, but the Buccaneers ranked third in the NFL both in total offense (397.9 yards per game) and points (28.6) and first in passing yards (302.8). Arians credits Leftwich’s tutelage for Jameis Winston passing for a league-high 5,109 yards and 33 touchdowns.

Of course, Winston also threw a league-leading 30 interceptions that season. Leftwich says the biggest regret of his coaching career is that he only got to work with the former No. 1 pick for eight months. He wishes they had more time together to hone Winston’s decision-making skills, but Leftwich couldn’t disagree with the Buccaneers’ decision to pursue Tom Brady.

Life with the GOAT got off to a rocky start. COVID-19 restrictions robbed Brady of the usual acclimation process offered by offseason practices and meetings. Arians says Brady didn’t fully grasp Tampa Bay’s offense until mid-November. He directed Leftwich to blend the aggressive downfield elements of Arians’ playbook with the up-tempo tenets that Brady thrived at executing during his storied Patriots career.

Things started to click in the final month of the season. After entering their Week 13 bye 7-5 and averaging 28.6 points a game, the Buccaneers returned with a revamped offense and reeled off eight straight victories (four to close out the regular season and four more en route to hoisting the Lombardi Trophy) while averaging 33.9 points a contest.

“He’s got a great work ethic, a great football IQ. It’s just been a growing process for both of us,” Brady said when asked about Leftwich during Super Bowl week. “It’s taken some time to get there because we didn’t have a lot of the things that we normally have with football (in the offseason). Over the last couple of months we’ve certainly executed a little bit better.”

Through a spokesperson, Fox Sports declined to make Brady available for this story.

The Bucs were better in 2021, averaging 406 yards and 30 points per contest. Leftwich believes they should have returned to the Super Bowl. But they fell in the divisional round of the playoffs to the L.A. Rams, who two games later won a championship of their own.

That offseason, Leftwich interviewed for head coaching openings with the Chicago Bears and Jacksonville Jaguars, the team that drafted him No. 7 in 2003. It was widely believed that Leftwich would receive a Jacksonville homecoming as the Jaguars’ head coach. But then came reports that Leftwich turned down the job because he didn’t want to work with general manager Trent Baalke.

Leftwich denies those claims. He says he had a good interview with the Jaguars and didn’t know Baalke.

“The stories started out of nowhere. I thought I was in a good spot, didn’t even talk to anybody. I understand this business, and I’m wise enough to know not to talk about what you’re going through when you’re going through it,” Leftwich says. “I never turned down that job because they never offered it. There were a lot of stories out there and I never spoke on it, but I never turned it down.”

Jacksonville eventually hired Doug Pederson, who had guided the Philadelphia Eagles to a Super Bowl victory five years earlier. Pederson guided the Jaguars to a playoff appearance in Year 1 but missed the playoffs in 2023 and is on the hot seat with Jacksonville at 4-12.

“I was willing and ready to take that (Jaguars) job,” Leftwich says. “That’s where I played, and I was very interested in trying to help that situation — all hands on deck — really trying to help that situation, because I know that city, I know the fan base and I thought that they had really good players down there that you can win football games with.

“But when I did the interviews … I knew that, ‘OK, at the end of the day, if I don’t get either, I get to go back with Mike Evans, Chris Godwin, and maybe (Brady, who was considering retirement) — people who I built strong relationships with.’ I was like, ‘I just get to go back to that and coach ball.’”

Brady retired, then unretired in February 2022. The next month, Arians retired abruptly, turning the team over to defensive coordinator Todd Bowles. It seemed like a seamless transition plan: Bowles would continue to oversee the defense while Leftwich and Brady ran the offense. But injuries ravaged the Buccaneers’ offensive line, and Brady, who was going through a highly publicized divorce, wasn’t as effective.

Tampa Bay’s offense plunged to 15th in yards (346.7) and 25th in points (18.4). After a first-round playoff exit, Brady retired for good and Bowles fired Leftwich.

“We didn’t score enough points and we didn’t run it well, and at times we didn’t throw it well,” Bowles said at the time when explaining his decision. “When you see something wrong, you have to try and fix it. I’ve been with those guys a long time, so it was a tough decision. But I felt the change had to be made.”

Arians, who had taken on an advisory role with the team, didn’t agree with the move. He is on record saying Brady’s personal matters hindered the quarterback’s play. And the former coach believes Leftwich became the scapegoat for the Buccaneers’ struggles.

“It looks like it all falls on Byron, and that to me is totally wrong,” Arians says. “I mean, it was just a different philosophy that Todd wanted to go with. … But if there is anyone that puts anything out negatively about Byron, they’re totally full of s—.”

The fallout from that season dramatically altered Leftwich’s coaching trajectory, but he says he understood Bowles’ decision. “I felt it was time to move on,” Leftwich says. “It was the first time we were out of the top five in offense. So the fact that we were 15th allowed people to say, finally, ‘Does that guy really know what he’s doing? Can he do this?’ … That’s the nature of the business.”

Leftwich doesn’t view the 2022 season as a total failure. Given the calamity he and his players faced and all of the mixing and matching he had to do to compensate, he views that season as his best coaching job. It forced him to grow.

“(Arians) always told me, ‘I’ve been fired for winning, I’ve been fired for losing. I’ve been fired for doing my best. I’ve been fired for doing my worst.’ So being fired means nothing,” Leftwich says. “You can’t worry about being fired. Believe in what you believe in, do what’s best for the players, and accept everything they could come with it.”

Following his Tampa Bay departure, he expected to receive inquiries, but no NFL teams called. He received some interest in college positions, but some of those would have required him to make what he believed were rushed decisions, so he declined. Others didn’t seem like good fits, so he embraced the opportunity to make up for lost time with his son.

Leftwich started 50 NFL games for four franchises after Jacksonville made him a top-10 pick in 2003. (Jamie Squire / Getty Images)

The body clock still chimes at 3 a.m. without the use of an alarm clock, just as it did during his coaching days. Instead of reporting to an office by 3:30 a.m. for film study, practice and game planning, he hits the weights, then the punching bags. By midmorning, after he feeds Dominic and gets him to school, Leftwich finds himself in front of a screen, clicker in hand.

He studies the coaches film of every NFL team. When watching live, he calls plays as if he were in the quarterback’s ear. Sometimes his predictions are correct, sometimes they’re not, but Leftwich makes the next call regardless. He digs deep to expand his knowledge of offensive and defensive patterns and tendencies, “staying sharp and up on what everybody’s doing.”

“He has a 360-degree perspective of the game — not only offense but defense as well,” Tomlin says. “Certain people have the ability to see the game in 3-D, and Byron is one of them.”

Leftwich says Arians taught him just as many nuances about interior offensive line play as he did pass routes and coverages. Arians also helped Leftwich learn the importance of understanding players’ capabilities, believing a firm grasp of each player’s skill set enables a good coach to design more expansive and versatile schemes while drawing greater confidence and commitment out of players.

“People get hung up on ‘The system this, the system that.’ I don’t care what the system is,” Leftwich says. “I know enough different types of offenses and different types of personnel packages and ways to attack to be able to … be as multiple as possible. And that’s all about preparation.

“It’s how (Arians) raised me. Anywhere I go, we’ll be as multiple as we need to be. We need to be two tight end set this week? Then it’s two tight end set. We need to be a four wide receiver set next week? We’ll do whatever we need to do to win that game. But because of our preparation, we will be able to do everything.”

Both Arians and Tomlin agree that Leftwich should be a member of an NFL coaching staff, if not leading his own. But to return to the NFL ranks, Leftwich has a series of questions he must answer.

A query of six front-office members who are expected to interview for general manager positions — and who are thus forming their own prospective head coach candidate lists — yielded mixed reviews. All agreed Leftwich exhibited great instincts and leadership abilities as a player. Some believed those strengths translated well to coaching and praised the abilities he showcased with Tampa Bay. Others expressed reservations about Leftwich’s independence.

How much of Tampa Bay’s success stemmed from Brady’s greatness, they wondered. How much of the offensive explosiveness was Leftwich responsible for, and how much came from Arians’ expertise and direction? How much of the drop-off in production in 2022 can be attributed to Arians’ absence?

Leftwich believes a deep dive into his qualifications and responsibilities in Tampa Bay will dispel any doubts. “I was blessed to have that opportunity in Tampa because the guy that hired me put a lot on me and I know how to do things the right way because of that,” he says. “I encourage anybody to do their background checks. Ask anyone who has worked with me.”

“I get a lot of credit for things I didn’t do in Tampa,” Arians says. “Byron called all the plays. Very seldom did I call anything. He did it all, even in the Super Bowl.”

Then there’s the recency question. In a league where head coaching tenures rarely exceed three years, hot prospects shoot up in popularity, then fade quickly into oblivion. Will Leftwich’s name still carry enough clout to garner consideration in a coaching market expected to feature head coaching veterans such as Mike Vrabel and Brian Flores and coordinators Ben Johnson, Aaron Glenn, Joe Brady and Kliff Kingsbury?

Leftwich recently hired a new agent and stressed his desire to aggressively pursue NFL jobs. He believes that if he meets with a team owner or general manager looking for a head coach — or a head coach looking for a coordinator — his credentials will elevate him above competing candidates.

“Just give me the opportunity. Bring me in and see. Communicate with me, see if I’m the right type of leader you want,” Leftwich says. “Do your homework. See if I can lead men. … See if I know my X’s and O’s. See if I know people. See if I know what needs to be done to succeed at the job.”

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; photos: Douglas P. DeFelice, Perry Knotts / Getty Images, Scott Boehm / Associated Press)