One day last summer, Harrison Barnes, a longtime N.B.A. veteran, was finishing up an off-season workout with Victor Wembanyama, his 7-foot-4, then-20-year-old San Antonio Spurs teammate and one of the league’s most dazzling young stars.

Barnes was new to the team — he had recently been traded from the Sacramento Kings — and new to Wembanyama. But he was already beginning to understand that Wembanyama was precocious in more than one way.

In the N.B.A., many teams track shooting percentages and shots made in games and at practice as a way of gauging their players’ progress. The Spurs had a chart that tracked both, but ranked players based on makes. Barnes told Wembanyama that metric felt insufficient. Wembanyama pondered Barnes’s concern. Then he got to work.

He picked up a marker and started to sketch out some thoughts on a white board. He wondered if a graph might be better than a chart and if it should include week-to-week changes. Wembanyama plotted ideas for three theoretical players, whom he labeled A, B and C. At one point, Barnes heard the word “coefficients.”

“He was really trying to wrap his mind around like, ‘How do you get better at that?’” Barnes said. “How do you chart what progress is?”

That day, Barnes saw into Wembanyama’s psyche — the sincere search for knowledge and human connection that he’s carried with him through the early part of his N.B.A. career. It leads to the kind of authenticity that marketers crave, and fans are drawn to.

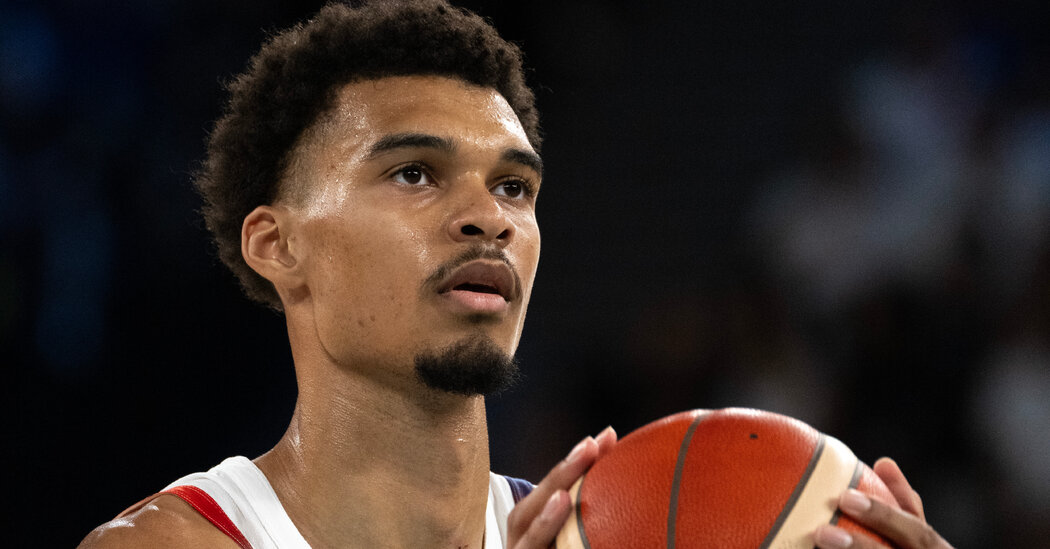

Wembanyama came into the N.B.A. from France as the most hyped prospect since LeBron James. He was taken first overall in the 2023 draft, and his play on the court has matched the early expectations. He can handle the ball like someone a foot shorter. He can dunk and shoot 3-pointers, generating debates about which he should do more. He is perhaps the most fearsome defender in the league, with an eight-foot wingspan that is nearly impassable.

As the N.B.A. confronts its future without an aging James and his contemporaries Stephen Curry and Kevin Durant, Wembanyama has embraced the idea that he will lead it, with his play and his endeavors off the court. And he has learned that the best way to present himself is to just be who he is, a person intensely focused on being a great basketball player, who also loves reading fantasy novels, playing chess and gathering all the knowledge he can about the world.

“Most of us want to craft a nice legacy and nice image because those are the things that people will remember,” Wembanyama, who turned 21 this month, said in a recent interview. “But on the other side, I think the best way for me to have the best image, and to give the right messages I want to send, is to be genuine. Just like not force myself to do things that don’t resemble me or to say things that I don’t believe in.”

As he spoke, he sat at a table in a plain conference room at a hotel in Milwaukee. It was a day off between games, and the Spurs had arrived a few hours earlier after taking a bus from Chicago. Wembanyama dressed comfortably, in a dusty rose-colored sweatsuit.

“I’m not in a hurry, but I make strategic choices,” Wembanyama said. “And I don’t hesitate turning down offers in the millions and millions of dollars just for something that I don’t believe in.”

It is an analog way of looking at life in a society that often is in a hurry. The youngest to accomplish something are often lionized, and impatience sets in if success is seen to take too long.

This is particularly true of the N.B.A., which many of the best players join when they are 18 or 19, and the inability to achieve immediately has dimmed many bright stars. The third pick in Wembanyama’s draft, 20-year-old Scoot Henderson of the Portland Trail Blazers, is already facing questions about whether he has what it takes to succeed in the league. Zion Williamson is 24, yet some are wondering if his marriage with the New Orleans Pelicans, who selected him first overall to much fanfare in 2019, has failed.

No one is asking those questions about Wembanyama.

He was the league’s rookie of the year last season and its leader in blocked shots per game. This season he became the first player in N.B.A. history to have more than 2,000 points, 1,000 rebounds and 200 3-pointers in his first 100 games. He is the betting favorite to be the league’s defensive player of the year, an award rarely won this early in one’s career.

“He cares about everything,” said Chris Paul, 39, the Spurs’ point guard who is learning French on the app Duolingo so he can try to speak to Wembanyama in his native language. “He cares about how he treats people. He cares about wins and losses. He cares about if he’s doing enough work.”

Wembanyama scored 50 points against the Washington Wizards in November, his first 50-point game and only the eighth 50-point game in Spurs history. After the game, he downplayed what he’d done, saying he hoped it was just one of many accomplishments he would have in his career.

Wembanyama knows he will eventually be judged by how many championships he wins, which seems just fine with him.

“He has larger ambitions,” Barnes said. “He is motivated by winning. He wants to be one of those guys who goes and wins an Olympic gold medal, he goes and wins an N.B.A. championship, that those are the things that really motivate him.”

Wembanyama’s arrival fits nicely with the N.B.A.’s ambition to be a global league.

Part of that involves playing games around the world, including in Paris. Since 2020, the N.B.A. has played four regular-season games there.

This week, in a first, Paris will host two regular-season games, when the Spurs and the Indiana Pacers play on Thursday and Saturday. On Tuesday, Wembanyama and the Spurs unveiled an outdoor court, which he designed and the team paid a significant portion of the cost for, in Le Chesnay, the Parisian suburb where he grew up.

Wembanyama has increased the Spurs’ popularity in France dramatically, and his jersey is the second-best selling N.B.A. uniform in Europe behind James. He is the league’s third-most viewed player on social media globally, trailing only James and Curry.

“I would say we haven’t seen anybody like this, especially from a European player, ever,” said George Aivazoglou, the N.B.A.’s managing director of Europe and the Middle East.

The N.B.A. has a long history of outstanding European players. The first to win the league’s Most Valuable Player Award was Germany’s Dirk Nowitzki, after the 2006-07 season. In five of the last six years, one of two European players, Greece’s Giannis Antetokounmpo and Serbia’s Nikola Jokic, have won the award. The other player to win during that stretch was Joel Embiid, who is from Cameroon. After his Milwaukee Bucks played the Spurs this month, Antetokounmpo said Wembanyama will “be a face of the league for a lot of years.”

Until recently the best players in the league — and certainly the biggest stars — have tended to be American. Even as Jokic, Antetokounmpo and Luka Doncic have become dominant on the court, nothing excites N.B.A. viewers like James facing Curry in the playoffs, regardless of whether their teams have a legitimate chance at a championship.

But the league bet early on Wembanyama and his ability to captivate fans.

His French team, Metropolitans 92, played a pair of exhibition games in Las Vegas against the G League Ignite in October 2022, which the N.B.A. helped organize. Wembanyama played brilliantly there. In the two games, he scored a combined 73 points, on 50 percent shooting, with nine 3-pointers, 15 rebounds and 9 blocked shots. After that, the rest of his Metropolitans 92 games were broadcast on the N.B.A. App so American fans could familiarize themselves with him.

Around then an upstart sports drink company called Barcode started hatching a plan to land Wembanyama as a partner.

Barcode was founded in 2020 by Bar Malik, who had worked with N.B.A. teams and players, and Kyle Kuzma, a forward for the Washington Wizards who then played for the Lakers. One of Barcode’s top investors was a businessman named Karim Maachi, who had a close relationship with Wembanyama’s agents.

Wembanyama said he relied on his agents, Bouna Ndiaye and Jeremy Medjana, the founders of the agency Comsport, and his marketing agent, Issa Mboh, Comsport’s head of global marketing, to filter offers.

“My goals in business with who I partner with is, it’s not money,” Wembanyama said. “The motivation is more to create an ecosystem of things that I can relate to and to create a legacy of things I want to leave behind me.”

He trusts that they know him well enough to choose the right opportunities. Before he entered the N.B.A., they spent months interviewing dozens of Wembanyama’s friends and family members to make sure they had a clear picture of who he was as a person.

“We want him to stay French,” Ndiaye said. “Because some of the international players, they go into the U.S. and they get Americanized. And we also want him to embrace the American culture because he lives in the U.S. He’ll live there for maybe all his life.”

Ndiaye said a marketer offered to pay $1 million for an hour of Wembanyama’s time to promote a brand at the All-Star game last year. But Ndiaye turned down the offer because it wasn’t a company with which they had a deeper relationship.

“We’ve turned down deals because he didn’t consume the product, like fast food or soda,” Mboh said. “The thing he would always say is, ‘I’m not going to promote something I don’t consume myself.’”

He added, “We’re not looking to have 100 partners, but a strong pool of partners that are with him in the long run.”

Wembanyama currently has deals with Nike and the French luxury fashion brand Louis Vuitton, both of which help him solve the problem of how someone so tall and thin can find clothes. He also works with the San Antonio-based grocery chain H-E-B, the sports merchandise company Fanatics and the video game NBA2K, all established brands with long histories of relationships with stars.

Barcode was not that type of company. It is now the official sports drink of the Spurs, the Brooklyn Nets and the Miami Heat, but back then it was an unproven startup. Maachi knew that could be a disadvantage when he first broached the idea of pursuing Wembanyama with Malik.

“We have about a 1 percent chance of getting him,” Maachi told Malik.

But why not try?

They made it past the agents’ screening. Then Malik made a presentation to Wembanyama over a video call in November 2022.

“It really spoke to me,” Wembanyama said. Watching from his apartment on the outskirts of Paris, he liked the product and the business plan.

A few months later, Malik and Wembanyama met at a coffee shop in Paris. Wembanyama arrived in the passenger seat of Medjana’s tiny Smart car (which Wembanyama insists is “surprisingly spacious”), amusing Malik as he emerged, unfolding his long spindly legs.

Then only 18, Wembanyama’s “serious demeanor” and focus impressed Malik.

“He just listens and he’s taking it in,” Malik said. “And he knows what he wants.”

He asked for equity in the company and now has the second largest stake next to Malik. He is also the face of the brand. The successful effort to sign Wembanyama made Maachi think of “Air,” the movie about how Nike signed Michael Jordan.

In the conference room in Milwaukee, Wembanyama was told about Maachi’s comparison. He raised his eyebrows, smiled a little and exhaled sharply.

“That’s funny,” Wembanyama said. “I sure hope I can have the same kind of impact. Of course.”

The partnership between Nike and Michael Jordan was transformative for both, as Jordan became the best to ever play the game.

Is that Wembanyama’s goal? He hesitated.

“So,” he said, then hesitated for several seconds more.

“I’m a superstitious person,” he said. “I don’t talk about my — I don’t say my goals out loud.”

Wembanyama smiled sheepishly and noted it was a good way to answer this question, one he is sure to get again.

He has not had much media training, but he does think about how he interacts with the press. He sometimes reviews his answers in interviews to identify areas of improvement.

He taught himself English as a child because he knew that one day he wanted to play in the N.B.A. He believes that his proficiency in the language, though it may help him connect with American audiences, is less important than showing his personality, being driven and performing well on the court.

“In the first year, being a foreign player, it can limit the reach a little bit maybe,” Wembanyama said. “But it’s not a worry to have in the long run.”

And he does let people in to see his quirkier side.

When he came to New York in late December for a pair of games against the Knicks and the Nets, he asked the Spurs and Mboh to help him find a park in the city where he could play chess. On a cold, drizzly day, he told his followers on social media to meet him at the southwest corner of Washington Square Park, where he played a few games.

“I’m sure people want to keep me safe, would like me to stay in the cozy hotel room,” Wembanyama said. “I just, I’m human, you know. Just wanted to have fun.”

His public profile has grown though, so he didn’t take the subway there, as he did to a Yankees game before the draft.

“I wish!” he said.

In his postgame news conferences, Wembanyama rarely reaches for clichés. He recalled a time when he tried to give an answer to a question about French politics which he thought would please everyone.

“It didn’t work out, so I’ll never do it again,” he said.

But he understands why some of his N.B.A. peers speak in platitudes.

“I don’t blame them because it’s a lot,” Wembanyama said. “The truth is, after every game I do media, after every game, it’s an opportunity for me to fail.”

He added, laughing, “But I don’t think of failure that often. I’m not a pro at failing.”

He liked that line, too. Then he tried another.

“I fail at failing,” he said. He smiled again, having written his own perfect tagline.