For more than six years, Amazon Web Services, the world’s largest cloud computing company, provided technical support to deliver TikTok videos to tens of millions of Americans.

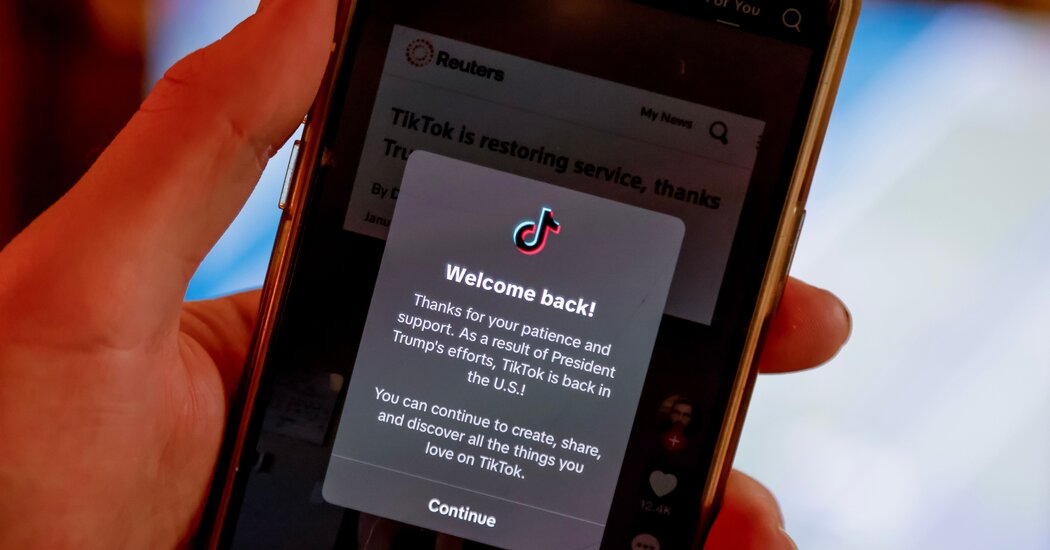

But over the weekend, Amazon faced a dilemma. A new law was taking effect banning TikTok, owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, in the United States. Tech companies were barred from distributing and updating it or they would face financial penalties. At the same time, President-elect Donald J. Trump was telling tech companies he planned to pause enforcement of the law with an executive order.

Just hours before the ban took effect, Amazon appeared to comply with the law, according to a New York Times review of the way TikTok’s web traffic is handled. Instead, Akamai Technologies, a Massachusetts-based company that was already helping to deliver TikTok videos to phones, took over more of the technical support.

The change, which was picked up by digital forensics conducted by The Times, was one of the small behind-the scenes-maneuvers that showed how tech companies have diverged in their approach to the TikTok ban.

Apple and Google also chose to follow the law. They swiftly removed TikTok and other apps owned by ByteDance from their app stores. But Oracle, another tech giant, was still processing and serving TikTok user data. Akamai and Fastly, which speed processing times for TikTok videos, were also still doing so.

The schism highlights the dilemma the TikTok ban has forced on major American tech companies: risk alienating a mercurial president who made his support for TikTok an extremely public part of his inaugural policymaking, or risk breaking federal law and face up to billions of dollars in penalties. Several legal experts said it was unclear whether Mr. Trump’s executive order shields companies from the law’s monetary penalties or potential lawsuits.

“On one hand, you have this massive theoretical liability of up to $850 billion and on the other side, you have the potential benefits of complying with Trump’s wishes and being in his good graces,” said Neil Suri, an analyst at Capstone, a policy research firm.

The tech companies made different assessment of that risk. Apple did not believe Mr. Trump’s executive order would be enough to override their responsibility to follow the law, according to two people who spoke with Apple representatives about its plans but didn’t have permission to speak publicly. Google reached a similar decision, said one of these people, who also spoke to its representatives, and a person familiar with the company’s thinking.

Oracle and others had been hesitant to violate the law under the Biden administration, said two people involved in their work over the weekend who didn’t have permission to speak publicly — a key reason the app stopped working for half a day over the weekend, when the ban took effect.

But they believed that the promise of an executive order from Mr. Trump carried new power, prompting them to help the app restart operations in the United States, the people said.

Amazon, Fastly and TikTok didn’t respond to requests to comment. Google, Apple, Oracle and Akamai declined to comment.

The different responses appear to be driven by money, politics and fear.

Apple and Google were under intense scrutiny in the weeks leading up to the TikTok ban. They control the software that powers millions of American smartphones.

They also have a financial interest in the app, as they profit from TikTok’s use of their in-app payment services. Last year, Apple made $354 million in fees from TikTok, while Google collected $63 million, according to Appfigures, a market research firm focused on the app industry. That was mainly through digital coins on TikTok that users can purchase and gift to creators that they like, the firm said.

But removing the app would be consistent with the positions Apple and Google had taken in the past, around the world, to follow the laws of the countries where they operate.

And it was likely that TikTok could survive for several months without their support. Over the years, TikTok has shifted much of the operation of the app to servers, primarily run by Oracle, so that it relies less on smartphone software, said Ariel Michaeli, the founder of Appfigures. He said that it also updated the app in the days before the ban, delivering the latest version at the last possible moment.

Oracle and Akamai both told investors that they stand to lose significant sales and profits if they stop hosting and distributing TikTok content.

They also play critical roles in making sure the TikTok app is operational. If they stop working with TikTok, the app wouldn’t function and an outcry would follow. Much of the internet exploded on Saturday and Sunday when TikTok briefly went dark.

Oracle also has a uniquely close relationship with Mr. Trump and with TikTok. Larry Ellison, the company’s founder and chief technology officer, joined Mr. Trump for an announcement on Tuesday about a new $100 billion artificial intelligence initiative. At the event, Mr. Trump mentioned that Elon Musk or Oracle could buy TikTok and emphasized his “right to make a deal.”

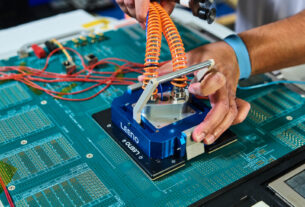

Oracle also works with TikTok to store sensitive U.S. user data and has been in talks with TikTok to help review the company’s video recommendations in the United States as part of a broader security plan.

Amazon’s role was small but important. It had been hosting a critical piece of data, called a Domain Name Service record, that directs hundreds of millions of web browsers and smartphone apps to TikTok servers.

But the consequences of flouting the law, which was passed with wide bipartisan support in Congress and upheld unanimously by the Supreme Court, could be painful. Oracle and other companies could be opening themselves up to new liability by relying on the executive order, legal experts say. Mr. Trump could change his mind or selectively enforce the law against companies who fall from favor, and a future administration could later pursue financial penalties under the law’s timeline, they say.

Senator Tom Cotton, Republican of Arkansas and chairman of the Senate’s intelligence committee, made calls to some major tech companies in the last week to say that they needed to comply with the law. He said on X that they could face “hundreds of billions of dollars of ruinous liability under the law,” not just from the federal government but also if state attorneys general moved to enforce it, or if shareholders sued over the decision to violate it.

Senator John Thune, Republican of South Dakota and the majority leader, said this week that “the law is the law” and “ultimately it’s going to have to be followed.”

A group of TikTok users or social media companies like Meta or Snap could also bring lawsuits challenging the executive order. Users could argue that the U.S. government was inadequately protecting their data by failing to enforce the statute, Capstone analysts wrote, saying that was the likeliest type of lawsuit to emerge.

“Oracle is making the calculus that the probability they are held liable is quite minimal,” Mr. Suri of Capstone said. “Obviously, Apple and Google haven’t made that calculus. That’s a matter of them seeing the risk-reward differently.”

David McCabe and Nico Grant contributed reporting.