The world’s largest gathering of mathematicians convened in Seattle from Jan. 8 to Jan. 11 — 5,444 mathematicians, 3,272 talks. This year the program diverged somewhat from the its traditional kaleidoscopic panorama. An official theme, “Mathematics in the Age of A.I.,” was set by Bryna Kra, the president of the American Mathematical Society, which hosts the event in collaboration with 16 partner organizations. In one configuration or another, the meeting, called the Joint Mathematics Meetings, or the J.M.M., has been held more or less annually for over a century.

Dr. Kra intended the A.I. theme as a “wake-up call.” “A.I. is something that is in our lives, and it’s time to start thinking about how it impacts your teaching, your students, your research,” she said in an interview with The New York Times. “What does it mean to have A.I. as a co-author? These are the kinds of questions that we have to grapple with.”

On the second evening, Yann LeCun, the chief A.I. scientist at Meta, gave a keynote lecture titled “Mathematical Obstacles on the Way to Human-Level A.I.” Dr. LeCun got a bit into the technical weeds, but there were digestible tidbits.

“The current state of machine learning is that it sucks,” he said during the lecture, to much chortling. “Never mind humans, never mind trying to reproduce mathematicians or scientists; we can’t even reproduce what a cat can do.”

Instead of the generative large language models powering chatbots, he argued, a “large-scale world model” would be the better bet for advancing and improving the technology. Such a system, he said in an interview after the lecture, “can reason and plan because it has a mental model of the world that predicts consequences of its action.” But there are obstacles, he admitted — some mathematically intractable problems, their solutions nowhere in sight.

Deirdre Haskell, the director of the Fields Institute for Research in Mathematical Sciences in Toronto and a mathematician at McMaster University, said she appreciated Dr. LeCun’s reminder that, as she recalled, “the way we use the term A.I. today is only one way of possibly having an ‘artificial intelligence.’”

Dr. LeCun had noted in his lecture that the term artificial general intelligence, or A.G.I. — a machine with human-level intelligence — was a misnomer. Humans “do not have general intelligence at all,” he said. “We’re extremely specialized.” The preferred term at Meta, he said, is “advanced machine intelligence,” or AMI — “we pronounce it ‘ami,’ which means friend in French.”

Dr. Haskell was already sold on the importance of “using A.I. to do math, and the huge problem of understanding the math of A.I.” An expert in mathematical logic, she is working on the equivalent of a textbook: a collection of results that can be used by A.I. systems to generate and verify more complex mathematical research and proofs.

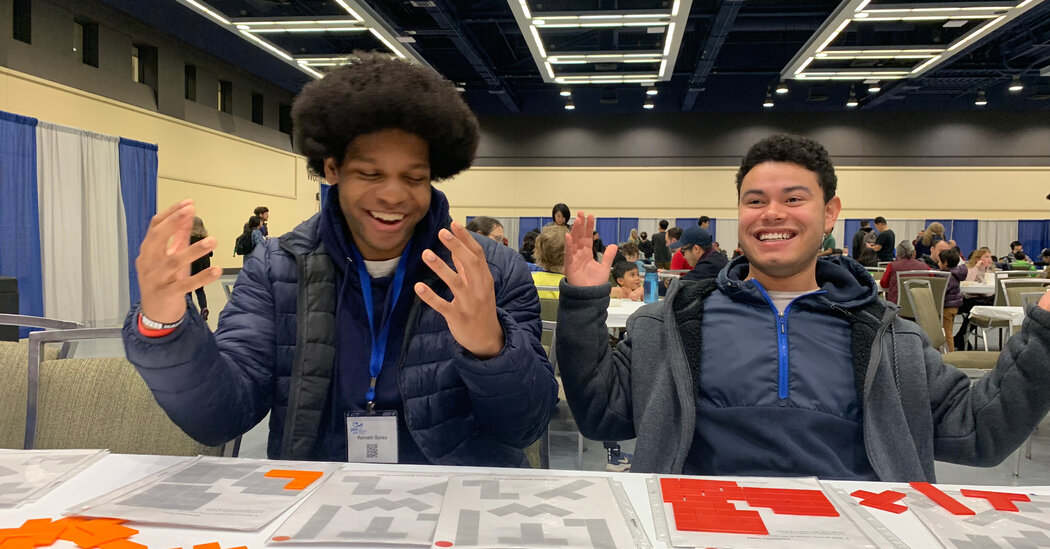

For Kenny Banks, an undergraduate at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro who attended the J.M.M., artificial intelligence does not appeal as a tool for guiding exploration. “I think the mathematics that people currently love is driven by human curiosity, and what computers find interesting cannot be the same as what humans find interesting,” he said in an email. Nevertheless, he regretted not squeezing any A.I.-related talks into his itinerary. “The math + A.I. theme was definitely of interest, it just ended up not working with all the things I had planned!”

Here are some other highlights from the mathapalooza in Seattle:

Day 1

At 6 p.m. on Wednesday, Jan. 8, after a ribbon-cutting and awards ceremony, attendees stampeded to the grand-opening reception in an exhibit hall. The draw was a) free food, and b) exhibitor booths occupied by publishers and purveyors of various mathy wares. At Booth 337, Robert Fathauer was selling an impressive inventory of dice — including the new “5-Player Go First Dice,” a colorful set of five 60-sided dice that share no number in common, allowing five game players an equal shot when they roll to determine who starts first. Dr. Fathauer, who is based in Arizona, was also co-organizer of the meeting’s art exhibit and contributed two ceramic sculptures of his own, “Hyperbolic Helicoid” and “Cubic Squeeze.”

The exhibit’s award-winning art submissions were “Saddle Monster,” crocheted in wool, copper and nylon, by Shiying Dong of Greenwich, Conn., a mathematical artist with a Ph.D. in physics …

… and “Twisted” and “Untwisted,” created using a vector graphics app on an iPad, by Rashmi Sunder-Raj, a mathematical artist in Waterloo, Ontario.

Rebecca Lin, a Ph.D. student in computer science at M.I.T., received an honorable mention for a laser-cut engraving on paper titled “Disintegrating (State of Mind).”

Day 2

On Thursday, Jon Wild, a music theorist at McGill University in Montreal who does math on the side, was invited to a session on applied mathematics to discuss his investigations into “counting arrangements of circles” in the plane. Given certain constraints, there is one way to draw one circle, three ways to draw two circles, 14 ways to draw three, 173 ways for four, and 16,951 ways to draw five. (The enumeration of six circles is yet to be computed.) Dr. Wild was surprised to learn that this research was relevant to 3-D printing: that is, to how multiple printer heads could each trace circular arcs while avoiding collisions. “I was tickled,” Dr. Wild said.

During a session on mathematics and the arts, Susan Goldstine, a mathematician at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, lectured about her “Poincaré Blues” craft project. Named for the French mathematician Henri Poincaré, the project involved making a patchwork denim skirt from old jeans. As she described in a write-up: “After noodling around with different patterns, I settled on the tiling of the Poincaré disk model of the hyperbolic plane by 30º-45º-90º triangles,” which was familiar to her from an illustration by the classical geometer H.S.M. Coxeter (and which also inspired the Dutch artist M.C. Escher).

Day 3

At midday, the undergraduate poster session buzzed with expositions on topics including lunar time synchronization; the math of piano tuning; loops in four-dimensional space; and a model for wildfire containment, smoke spread and their public health consequences.

During another session on mathematics and the arts, Barry Cipra, a mathematician from Minnesota, gave a talk about “gelbes feld” (“yellow field”), a painting by the Bauhaus-trained Swiss artist Max Bill.

It may appear to be a solid canvas of color, Dr. Cipra said, but there is a faint pattern of contrasting dots, or, more precisely, squares. “Let’s look at an abstract version of Bill’s abstract,” he said. “Can you spot what Bill is up to?”

By Dr. Cipra’s analysis, the artist encoded in the painting a classic 3-by-3 magic square — a square array of numbers that form a logic puzzle wherein the sum of each row, column and diagonal equals 15.

Another peculiarity was that each row, column and diagonal had five pips (as on dice or dominoes):

Dr. Cipra noted, “It looks like Bill posed and solved an original mathematics problem and hid it in a painting: Can you place the pips within each square of the 3-by-3 magic square so that there are exactly five pips along each row, column and main diagonal of the 9-by-9 subgrid?” The same question could be asked for 5-by-5 and larger magic squares of odd sizes, he said. “But it’s far from clear what the answer is going to be.”

Dr. Goldstine found Dr. Cipra’s discovery compelling. “I am always excited when math turns up in a place where you wouldn’t expect it,” she said in an email. “I often use these surprising connections to get students who might be afraid of or bored by math to see some of its beauty.”

Day 4

The final day offered a number of public events, including a mini math festival with hands-on puzzles and games.

“Why is it math?” asked Aleksandra Upton, 7, of a geometric puzzle.

“Because we can count all the different ways that we put the shapes together,” said her mother, Karolina Sarnowska-Upton, a software engineering manager at Microsoft in Redmond, Wash.

In one public lecture, Ravi Vakil, a mathematician at Stanford and the incoming president of the American Mathematical Society, explored the simultaneously playful and profound “mathematics of doodling.”

In another, Eugenia Cheng, a mathematician and pianist at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, addressed “Math, Art, Social Justice.” One of her salient messages: “Pure mathematics is a framework for agreeing on things.” She sang some of the lecture alongside a recorded video of herself playing the piano.

And there was a world premiere of a documentary film, “Creating Pathways,” the second in the “Journeys of Black Mathematicians” series by the director George Csicsery. (It airs on public television stations in February.) The film’s senior consultant was Johnny Houston, an emeritus professor at Elizabeth City State University in North Carolina. After the screening, Dr. Houston remarked on the timeliness of the 2025 premiere: In 1925, Elbert Frank Cox became the first African American — and first Black person in the world — to receive a Ph.D. in mathematics. Of his own journey, and that of many Black mathematicians, Dr. Houston said that with exposure, experience and opportunity, “we can do as well as any mathematician in earning a Ph.D. and beyond.”

The last of the talks wound down that evening. By 3 a.m. the next morning, as some attendees headed to the airport, two mathematicians were just heading to bed, but not before riding the elevator down to the hotel lobby to ask reception for a late checkout.