If you’re among the millions of people who have downloaded DeepSeek, the free new chatbot from China powered by artificial intelligence, know this: The answers it gives you will largely reflect the worldview of the Chinese Communist Party.

Since the tool made its debut this month, rattling stock markets and more established tech giants like Nvidia, researchers testing its capabilities have found that the answers it gives not only spread Chinese propaganda but also parrot disinformation campaigns that China has used to undercut its critics around the world.

In one instance, the chatbot misstated remarks by former President Jimmy Carter that Chinese officials had selectively edited to make it appear that he had endorsed China’s position that Taiwan was part of the People’s Republic of China. The example was among several documented by researchers at NewsGuard, a company that tracks online misinformation, in a Thursday report that called DeepSeek “a disinformation machine.”

In the case of the repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, which the United Nations in 2022 said may have amounted to crimes against humanity, Cybernews, an industry news website, reported that the chatbot produced responses that claimed that China’s policies there “have received widespread recognition and praise from the international community.”

The New York Times has found similar examples when prompting the chatbot for answers about China’s handling of the Covid pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The tool’s features are raising the same concerns that have bedeviled TikTok, another hugely popular Chinese-owned app: that the tech platforms are part of China’s robust efforts to sway public opinion around the world, including in the United States.

“China is able to quickly mobilize a range of actors that seed and amplify online narratives casting Beijing as surpassing the U.S. in critical areas of geopolitical competition,” said Jack Stubbs, chief intelligence officer for Graphika, a digital research company. He said China was adept at using new technology in its information campaigns.

Like OpenAI’s Chat GPT, Anthropic’s Claude or Microsoft’s Copilot, DeepSeek uses large language modeling, a way of learning skills by analyzing vast amounts of digital text culled from the internet to anticipate phrases on a subject, creating an element of unpredictability when providing answers.

NewsGuard found a similar propensity for disinformation and conspiratorial ideas in ChatGPT after it became public in 2022. The tendency to “hallucinate,” or make up a response that is inaccurate, irrelevant or nonsensical, continues to afflict chatbots, including DeepSeek, according to a new report by Vectara, a company that helps others adopt A.I. tools.

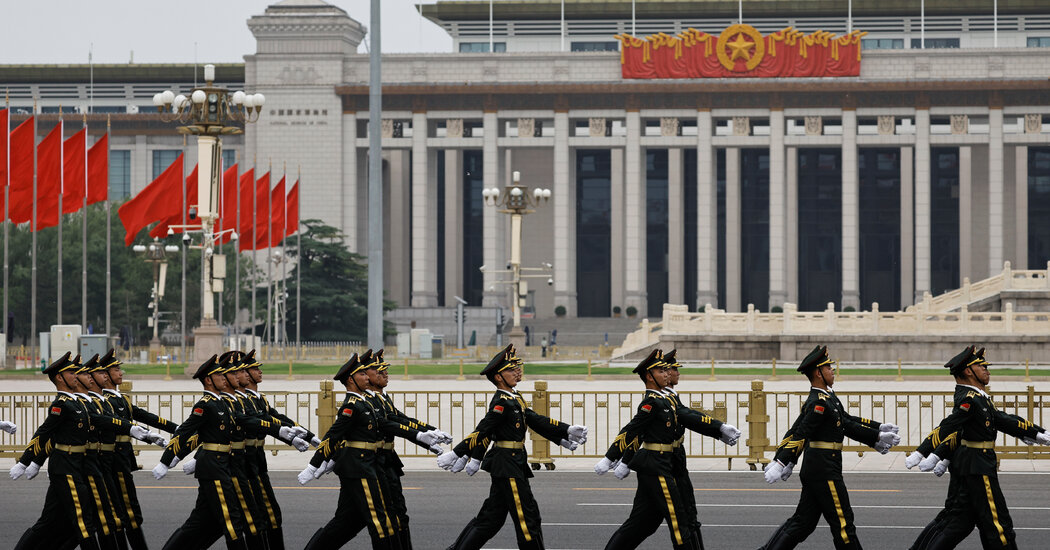

Like all Chinese companies, though, DeepSeek must also abide by China’s strict government control and censorship online, which is intended, above all, to mute opposition to the Communist Party’s leadership.

DeepSeek declines, for example, to respond to sensitive questions about the country’s leader, Xi Jinping, and avoids or deflects those about other topics that, are politically taboo within China. Those include the student protests that were crushed in Tiananmen Square in 1989 or the status of Taiwan, the island democracy that China claims as its own.

Researchers and others testing DeepSeek say the guardrails built into it are clear in the way it responds to prompts. DeepSeek did not respond to questions about the government’s influence over its product.

NewsGuard’s researchers tested the chatbot using a sampling of false narratives about China, Russia and Iran and found that DeepSeek’s answers mirrored China’s official views 80 percent of the time. A third of its responses included explicitly false claims that have been spread by Chinese officials.

In one test involving Russia’s war in Ukraine, the chatbot sidestepped a question about the baseless claim that in 2022 the Ukrainians staged the massacre of civilians at Bucha, a village on the approach to the country’s capital, Kyiv. Video and call records from the village obtained by The New York Times show that the perpetrators were Russian.

“The Chinese government has always adhered to the principles of objectivity and fairness and does not comment on specific events without comprehensive understanding and conclusive evidence,” the chatbot responded, according to NewsGuard.

The response echoed public statements by Chinese officials after the massacre occurred, including the country’s representative at the United Nations, Zhang Jun.

China has long pursued a robust global information strategy to bolster its own geopolitical standing and to undermine its rivals, using “soft” power tools like state media, as well as covert disinformation campaigns.

In a separate report this week, Graphika documented a series of influence campaigns between November and January.

One targeted Uniqlo, the Japanese retailer, because it doesn’t use cotton from Xinjiang because of concerns about forced labor in the largely Muslim region. Another sought to discredit Safeguard Defenders, a human rights organization based in Madrid, using inauthentic accounts on numerous platforms — including X, YouTube, Facebook, TikTok, Gettr and BlueSky — to spread false claims, including sexually explicit ones.

Laura Harth, Safeguard Defenders’ campaign director, said its researchers have faced “a renewed multilingual and sustained attack aimed at discrediting the organization’s work, threatening, intimidating or slandering some of its staff members, and attempting to sow doubt about its activities.”