ATLANTA — The elevator beeped, and the doors opened. We had arrived on the 17th floor.

Fluorescent white lights hung from the ceiling of the office space. The sun, peeking in on this scorching summer day, brightened the gray walls. Past the expansive lobby and down a skinny hallway was a room with a cracked door. When the man inside heard the knock, he blurted, “Come on in!”

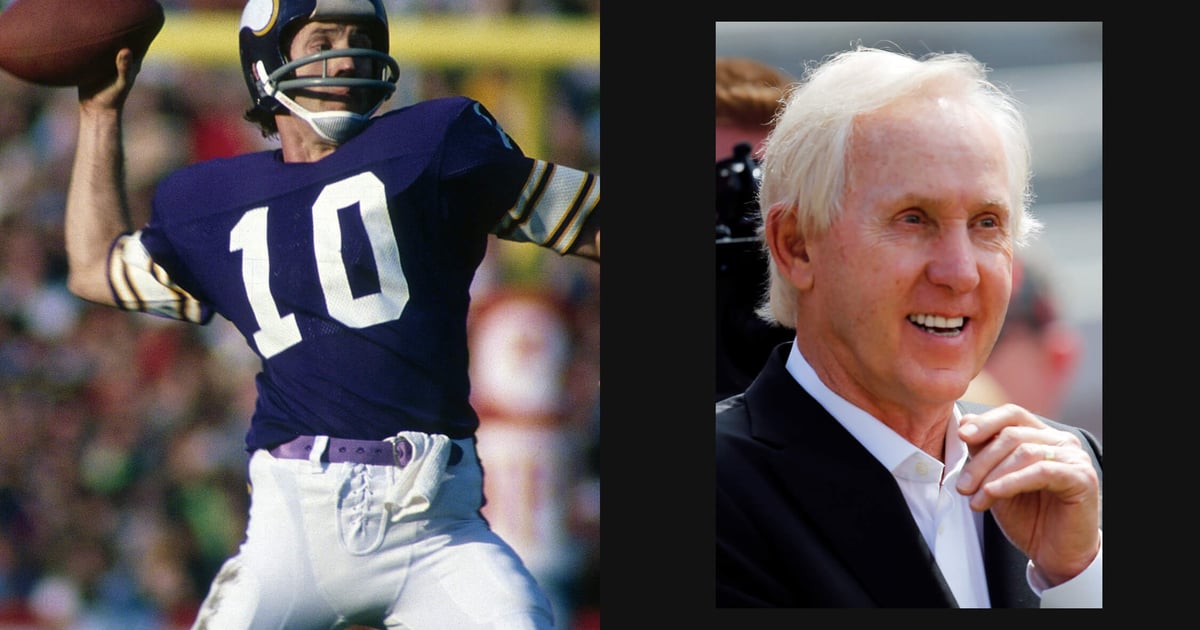

Fran Tarkenton’s glasses pressed up against the tip of his nose. He slouched in a chair, holding an iPad. Spotting me, he placed the tablet on his wooden desk, pulled the black frames off his face, set them down, then motioned toward the chair on the other side of the desk.

“Sit down!” he said. “What are you waiting for?”

On the wall behind him were dozens of framed photos: Tarkenton with revered Minnesota Vikings head coach Bud Grant, posing with the board of directors at Coca-Cola, standing next to former president George W. Bush. He didn’t acknowledge any of these pictures, the bobblehead of himself on his desk or the paintings leaning against the walls. He ran his hand through his wispy white hair and smiled.

He seemed amused, like he couldn’t wait to unfurl stories and explain why, at 84 years old — 63 years after his NFL debut — he still drives to this building in Buckhead to work almost daily. He would talk for hours, mentioning business titans (Warren Buffett and Steve Jobs), NFL players (Patrick Mahomes and Kirk Cousins), famed football coaches (Nick Saban and George Halas) and golf courses (Augusta National and Pebble Beach) in a fluid conversation that did not exhaust him for a second.

Tarkenton cursed, shrieked, eye-rolled and laughed. He even considered what it would be like to attend Week 1’s Vikings-New York Giants game as part of the latter team’s 100-year anniversary ceremony.

They’d asked him to go, which makes sense considering he is a Pro Football Hall of Famer who made four Pro Bowls with the Giants. That they played the Vikings, the franchise that bookended Tarkenton’s career and watched him set every significant NFL passing record at the time of his retirement, only made the trip to New York more sensible.

“I’m not going,” he said.

Why?

“I don’t need to do that,” he added, contorting his face and waving like a beauty queen atop a parade float. “I don’t have any interest,” he said plainly.

He’d rather work.

Tarkenton was scribbling his signature on a purple No. 10 jersey. When he finished, he handed the silver-inked Sharpie to one of his employees and immediately returned to our conversation as if he’d placed a bookmark in it and knew exactly where he’d left off.

He found his way to the subject of scrambling — of course he did. Search the internet for Tarkenton highlights, and you’ll find grainy footage of this tiny, 6-foot, 190-pound quarterback, dropping back in the pocket, spinning around, running to his left, sprinting back to his right and looking, play after play, like he was a father playing keep-away from his kids.

Tarkenton became known as “The Scrambler” or “Scramblin’ Fran” and was, in a roundabout way, Mahomes before Mahomes. Just like with Mahomes, who regularly and unbelievably escapes from defenders to fling the ball downfield, if you could find Tarkenton on television, you tuned in because the circus could begin at any time.

How do you think your scrambling would have gone over in today’s game?

“I would be more successful today,” Tarkenton said.

Why?

“Because the field is spread out more,” Tarkenton said. “I watch Patrick Mahomes. Patrick Mahomes doesn’t do anything I didn’t do. Nothing.”

You mea—

“Nothing,” Tarkenton interrupted. “I was just the first one who did it … with a fullback and two halfbacks!”

I invented scrambling. The two best quarterbacks this year played against each other in the Super Bowl. They’re both scramblers, and that started with me! pic.twitter.com/6bmwuHuoE6

— Francis Tarkenton (@Fran_Tarkenton) February 21, 2023

Necessity, the saying goes, is the mother of invention. And here was Tarkenton’s need as a child: to avoid getting pummeled into the pavement in a small alley behind his family’s apartment in Washington D.C.

His parents were preachers, and during the day, Tarkenton played with his brothers and evaded them by reversing, moving sideways and ducking them on the streets. Years later, after the family moved to Athens, Ga., and Tarkenton attended high school, a new need surfaced. Tarkenton, a quarterback at Athens High, attempted a tackle in practice and felt a pain in his right shoulder like he was being sliced open with a knife. Throwing hurt his shoulder, but he refused to sit out.

So he ran.

Once he secured the starting job at the University of Georgia and later as a third-round pick of the Vikings, the attribute prevented him from being swallowed up by defensive linemen. Once, in 1966, he scrambled for nearly 14 seconds, drifting left, then backward, then right, then back left, then back right again. The pass, which was tipped and caught in the end zone, ranked as one of the greatest 100 plays in NFL history.

Tarkenton retired in 1978 with the most rushing attempts (675) and rushing yards among QBs (3,674) in NFL history. How much has the game evolved since then? Well, four quarterbacks have amassed more attempts and yards in the last decade than in Tarkenton’s entire career.

“I don’t think you can play quarterback today without being mobile,” Tarkenton said. “Kirk Cousins has played really well the last four years and he’s not mobile. And I get on his ass about it.”

Really?

“Yes,” Tarkenton said. “I say to him, ‘Run! Pick up a first down! Quit standing there!’”

You yell that at the television? Or you’ve told him that?

“I tell him!” Tarkenton said. “He’s come and sat right where you are. He’s here in Atlanta now.”

So you keep up with it?

“Oh, I watch the games every weekend!” Tarkenton said. “I’d still play if I could!”

At the urging of a close family friend, Tarkenton attended the University of Georgia even though the Bulldogs had already secured commitments from two more highly regarded recruits. Tarkenton sat for a year and nearly transferred but ultimately stayed.

He stood on the sideline at the 1958 season opener against Texas and observed restlessly for three quarters. He frequently sidled up to the coaches and said, “I can do it, I can get you a touchdown in this game,” and they swatted him away like a gnat buzzing around their face.

In the fourth quarter, as legend goes, he sprinted out toward the huddle on his own volition. Georgia’s coach, Wally Butts, did not have time to pull him back. Tarkenton had taken a risk and made good on it, driving the Bulldogs down the field for a touchdown, inciting a loud cry from the fan base for the local boy to be a starter.

Twice during his NFL career, Tarkenton created pathways for the team he was playing for to trade him. This was long before agents disclosed trade requests to the media, before players realized they had the power to chart their own futures. Tarkenton pushed the envelope in ways that are eerily familiar to moves made almost 50 years later.

In the spring of 1966, having played five seasons in Minnesota for head coach Norm Van Brocklin, Tarkenton boarded a plane to Minneapolis, entered the team facility, walked into Van Brocklin’s office and said, “I ain’t playing here anymore. I’m not playing for you.”

“Why?” Van Brocklin responded.

“Because I have no faith or trust in you,” Tarkenton said. “You don’t want a quarterback who doesn’t believe in you.”

Their relationship had been rocky from the beginning. Ahead of the expansion Vikings’ first game in 1961, 63 years ago Tuesday, Van Brocklin told Tarkenton he’d be the starter. Then, in the locker room before kickoff, Van Brocklin said he’d decided to start George Shaw, a more experienced veteran.

“F— you,” Tarkenton told Van Brocklin at his locker. Later that afternoon, Tarkenton replaced Shaw and spurred the Vikings to a 37-13 victory.

#OTD 63 years ago, the @Vikings played their first @NFL game. Hall of Famer Fran Tarkenton came off the bench in his debut, throwing for four touchdowns and rushing for another, leading Minnesota to a 37-13 victory over the Chicago Bears. pic.twitter.com/gv7URFkgBl

— Pro Football Hall of Fame (@ProFootballHOF) September 17, 2024

Elevating the win was the fact that the Vikings had spotted a cameraman at practice during the week. They believed legendary Bears coach George Halas had dispatched the staffer to record the Vikings’ plays. “He cheated!” Tarkenton claimed.

Tarkenton’s initial success did not eliminate the lack of trust between him and Van Brocklin, and by 1966, the Giants ponied up four draft picks for the quarterback, including two first-rounders. Tarkenton enjoyed the glitz and glamour of New York, but in the end, the team’s struggles dragged him down. Once, shortly after Joe Namath had risen to prominence with the Jets, Giants owner Wellington Mara asked Tarkenton to come into his office for a meeting.

“Can you cut your hair real short?” the owner asked.

“Cut my hair? Why?” Tarkenton responded.

“We want you to be the anti-Namath,” Mara said.

“I don’t want to be the anti-Namath,” Tarkenton quipped. “I came here to win football games!”

“I want the image,” Mara said.

“The image?” Tarkenton asked. “I think you can help me with that. We’ve got to play the Cowboys twice a year. They have a defensive tackle named Bob Lilly and a linebacker named Lee Roy Jordan. We need players like that!”

Retelling the story, and the ensuing conversation with Mara that spurred a trade back to Minnesota, Tarkenton giggled. He would have the last laugh, playing in three Super Bowls for the Vikings and retiring with passing records (47,003 yards, 3,686 completions and 342 touchdowns) that he held for almost two decades.

“Do you think you can be too nice as a quarterback?” he asked.

Maybe. Is that a thing?

“Yes,” he said. “Remember, it all falls on your ass.”

“I can’t play football,” Tarkenton said. “So I do this.”

He waved his hand from left to right like a blackjack dealer asking for insurance on a potential 21.

Tarkenton is the founder of … Tarkenton, a company that partners with smaller companies mostly in the technology sector.

“We own eight companies and partner with five or six others,” Tarkenton said.

And you’re still invested in the day to day?

“If I’m not here,” he said, “I’m on the phone with them.”

When reminded he could be on the golf course every day, he was quick to respond: “I have too much fun doing this,” he said.

His love of business was instilled early. There was a grocery store near his family’s apartment in Washington D.C., and on Saturdays, he’d haul a wagon over. When customers exited the store, Tarkenton offered them the chance to place their groceries in his wagon. Many took him up on it and, when they reached their apartments, they’d hand him nickels, dimes and occasionally quarters. At 8, he was hired to deliver newspapers.

Toting this money, he’d purchase bubble gum cards of his sports heroes. In college, during the summers, he huddled chickens on a farm. In the NFL, during the offseasons, he knocked on doors and offered truck-shipping services. His first NFL contract paid him $12,500 in 1961. Eighteen years later, he was making $180,000, the largest contract in the NFL. But he wasn’t satisfied.

Maybe that’s because he never won the NFL’s ultimate prize. Tarkenton led the Vikings to three Super Bowls (VIII, IX, XI), all of them losses. “A tragedy,” he said.

He has replayed the scenes of those games too many times to remember, but the one aspect he returns to most often is the preparation. In those days, teams usually had an extra week to prepare for the game, and it was always Grant’s perspective, according to Tarkenton, that they’d be fresher with a week off. Was that the right approach? It’s anyone’s guess, but Tarkenton wonders now, even if it was not so much top of mind when his career ended.

He waffled on whether or not to retire — sound familiar? — and then ultimately decided to call it quits, creating a pathway into entertainment. He hosted a reality show called “That’s Incredible!” He was a commentator on “Monday Night Football.” He steeped himself in sales and marketing with Coca-Cola, where he met Buffett’s son. Then in 1996, he started his own company that specialized in digital marketing.

“Last year, somebody interviewed 1,500 billionaires, asked them what their No. 1 goal was and wrote about it,” Tarkenton said. “You know what the most common No. 1 goal was? They don’t want to lose money.”

Eight years ago, he became interested in Apple. He moved most of his investments there and said he reads two hours a day about the company on his iPad.

“See this here?” he asked, lifting a piece of paper and showing it to me. “That’s the price of Apple (stock) this morning at 9:50 a.m.,” he said. “$228.496.”

You wrote that down?

“Yeah,” he said. “And when you get out of here, I’ll go back and check it again.”

You check it multiple times a day?

“I would say I check it 20 times a day,” he said. “Because it’s fun!”

I celebrated 84 years of life on Saturday. I couldn’t be more excited about where I’m at today and the potential for the future! pic.twitter.com/867UWf4Mxh

— Francis Tarkenton (@Fran_Tarkenton) February 5, 2024

Tarkenton has been traveling. He went to Paris with his wife, Linda. He stayed at his lake house, where he lives close to Saban, who has become a close friend. He even played golf at Pebble Beach.

“My last hole-in-one was in 2022,” he said. “At Pebble. I had one at Augusta National, too, years ago. I asked the guys at Augusta and Pebble how many people have had a hole-in-one at both courses. Small number,” he said, smiling because he knows how he’s coming off.

It was confidence bordering on arrogance. Tarkenton often blurs this line, and who could blame him? He went from preacher’s son near the country’s capital to a symbol of hope at a huge university in the South. He went from third-round draft pick to one of the most recognizable athletes of his generation.

He acted brashly, and it worked. He wanted to make money and he did. Now eight decades in life’s pursuit, he liked going where he wanted to go, doing what he wanted to do, telling the stories he wanted to tell. And who could blame him?

The most interesting aspect of it all was how vivid everything was. It felt like he could go for days, but he needed to get back to work. He walked up the narrow hallway and through the lobby. He pointed me toward the elevators.

One of his employees was about to press the down arrow, then quickly asked me, “How was he?”

Indescribable. How does anyone have that kind of energy at 84?

The employee pointed back at the office.

“This place and these people keep him sharp,” the employee said. “They keep him young.”

(Top photos: Focus on Sport / Getty Images, John Bazemore / Associated Press)